Metropolis (1927).

Metropolis: Julie Wosk

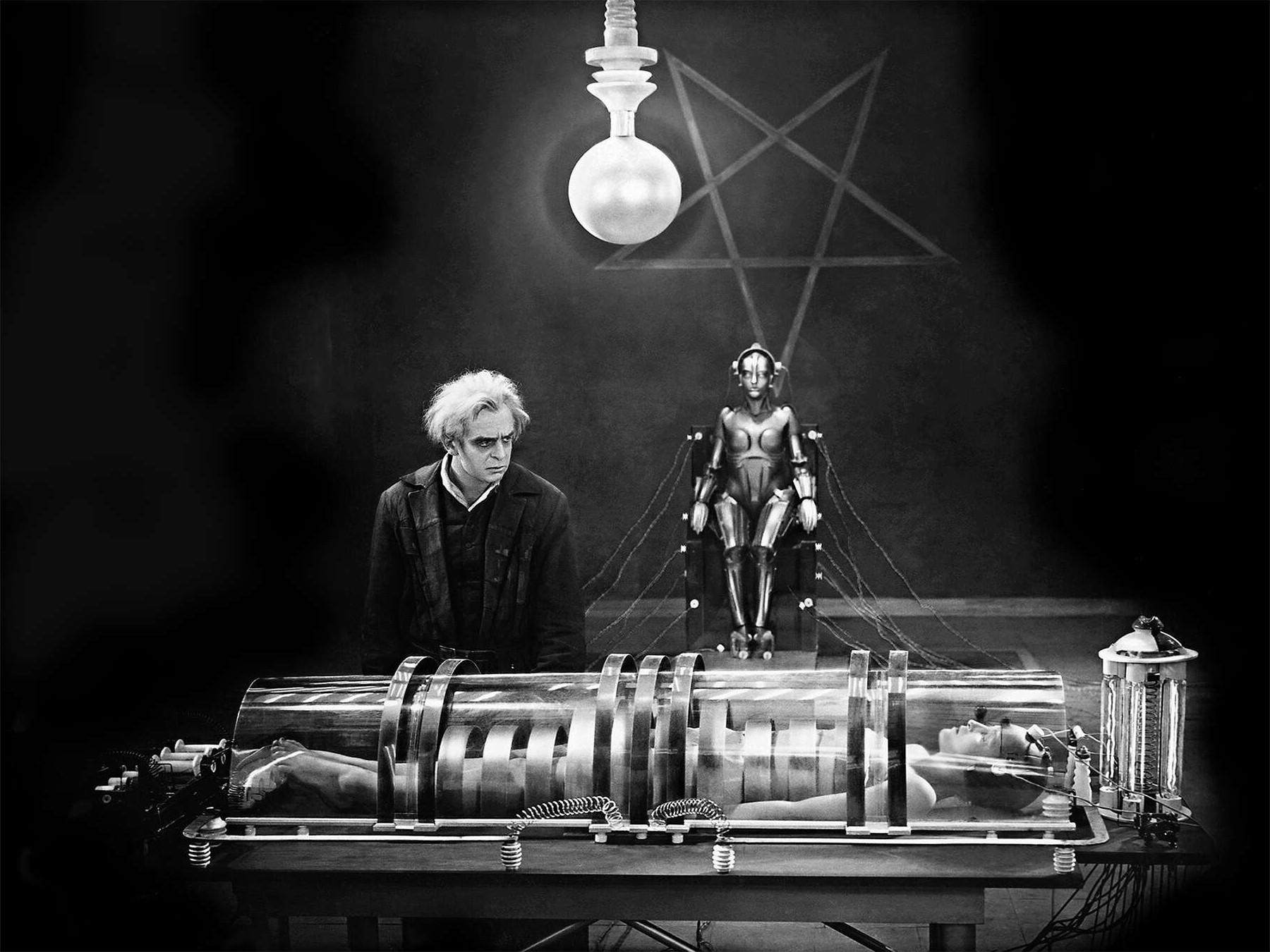

Gazing intently at the woman in a glass case, Rotwang, the mad scientist-inventor in Fritz Lang's classic silent film Metropolis (1927) is about to turn levers in his lab and launch a startling change: he will create an exact duplicate of the good-hearted Maria, who lies imprisoned with electrodes on her head. In this pivotal scene, pictured on the cover of this issue of T&C, Maria's features will soon be transferred to the wired metal robot in the background. A close-up of the robot's face magically dissolves into the face of Maria, her eyes suddenly open, and she turns into a dangerous temptress who will lead the city's workers astray.

With its dramatic, overheated plot, striking set designs, and innovative special effects, Metropolis is in many ways a film about the uses of science and technology to create transformations the transformation of the city into a marvel of modernity, the transformation of Metropolis's workers into robotic slaves, and the transformation of the saintly Maria into a diabolical and destructive femme fatale.

In the film, with its screenplay by Lang's wife Thea von Harbou, the "good" Maria offers kindness and comfort to the beleaguered workers, who move with numbing clock-like regularity in this ruthlessly industrialized world. Joh Fredersen, the master of Metropolis, fears that the workers might rebel and decides that Maria's influence must be undermined. He asks Rotwang to create a duplicate or false Maria to challenge the real Maria's credibility and destroy the workers' belief in her. Fredersen's son Freder, meanwhile, becomes entranced with the real Maria and horrified when Rotwang captures her to serve his evil purposes.

The facsimile or false Maria soon becomes an alluring siren at the city's upper-city Yoshiwara nightclub; she also leads the workers in the underground city in rampage where they smash the power station, causing flood. Later, the workers burn the false Maria at the stake, and at the film's end Maria is united with Freder, and the two, as well as Joh, join hands in reconciliation.

From its dramatic opening montage of pounding pistons to its brilliant scenic designs capturing the marvels of the modern city to its grim scenes of factory enslavement, Metropolis offers a revealing look at Lang's own conflicted and equivocal views of twentieth-century technology and mechanization. The futuristic, aboveground Metropolis, with its skyscrapers, airplanes, and streams of automobiles, is pictured as the essence of modernity and well-designed machine-age efficiency-a vision echoing the machine aesthetic seen in the art, architecture, and photography of the 1920s. In 1927, the same year Metropolis was first introduced to audiences in Berlin, the city of New York hosted the Machine-Age Exposition, in which visitors could admire the clean geometries of large ship propellers, steel ball bearings, and other emblems of modern technology on display.

Yet in a much more dystopian view, Lang's film also presents the Metropolis workers as mere cogs in the wheels of industry–men who have been turned into anonymous slaves whose rote actions mirror the movements of machines. The view is nightmarish: at the beginning of the film there is a destructive explosion in the machine rooms, and in a later, hallucinatory scene the Moloch Machine devours workers in its ghastly jaws.

But perhaps one of the most fascinating aspects of the film is how it portrays the creation of an artificial woman by using science and technology, as Rotwang's metallic female robot is transformed into Maria's demonic double. With his tousled shock of hair, his deranged eyes, and his lab full of bubbling beakers and electrical equipment, Rotwang is the film's archetypal mad scientist, a descendent of Mary Shelley's Dr. Frankenstein and a precursor of Dr. Pretorius in British director James Whale's campy 1935 film Bride of Frankenstein and Peter Sellers's later hilarious rendition of Dr. Strangelove in Stanley Kubrick's satirical film about the cold war.

In Metropolis, the robot, or Maschinenmensch, that Rotwang uses for the transformation was originally created as tribute to Hel, the woman Rotwang and Fredersen had once both loved, but who, after marrying Fredersen, had died giving birth to Freder.1 When he first created the robot, Rotwang had intended to give it Hel's own features. Now he decides to use it to create an android Maria, but in so doing, he plans to extract revenge on both Fredersen and Freder.

To start the transformation process, Rotwang turns on the electricity that sends rings of light moving up and down, encircling the robot's body, while flashing electrical discharges shoot toward Maria's body, which is lying in the glass tube. The remarkable special effects used to create this scene of transformation were produced and designed by Günther Rittau, who wrote about how he and the film's crew spent months in the lab with "photo-chemistry playing a major role": "We illuminated liquids in strange test-tubes and made them bubble, the electrical apparatus surrounding Maria was made to emit sparks and we gradually enveloped it in huge arcs of lightning, at the same time as rings of fire formed around the robot, moving up and down her body.”2 The rings were actually two circular, arched neon lights in tubes that were moved up and down by a type of elevator.

The film's lightning-like discharges were produced using a Tesla coil, a special-effects technique that was employed in silent films as early as 1915 and was used most famously in Whale's Frankenstein (1931). To the first film viewers who saw Metropolis in Berlin in 1927, and to the New Yorkers who in 1928 saw the much-edited version (cut by 25 per- cent from the original), the special effects must have seemed magical, and indeed the movie freely mixes references to technology, science, spirituality, and magic. (Lotte Eisner, in her study of Lang's films, reports that Lang said what interested him most in Metropolis was the conflict between the magical [the world of Rotwang) and the world of modern technology [Fredersen's world].3

In 1927, the same year of the movie's release, Hugo Gernsback's popular glossy American magazine Science and Invention included a story titled “’Metropolis’–A Movie Based on Science," which deconstructed the film's special effects and described the techniques used to portray Maria's transformation and the remarkable scenes of the industrial world, including "The maw of the huge machine which ruthlessly destroys body and soul." Gernsback's magazine itself freely mixed science and magic, and the same issues filled with stories about electricity, radios, and phonographs also included stories on mind-reading tricks and magic taught in schools.

Rotwang's creation of the robot version of Hel and his production of Maria's evil android tap into an ancient and recurring cultural theme: the quest to create an artificial human being. Legendary medieval tales of the golem created by Rabbi Loew in Prague, Dr. Frankenstein' feverish creation of the monster in Shelley's novel, the intricate eighteenth- and nineteenth-century mechanical automatons by clockmakers including Pierre and Henri-Louis Jaquet-Droz, and today's lifelike robots all suggest that the idea of creating an artificial human remains a captivating goal.

But the transformation of Maria also echoes another compelling theme: men's recurring fantasies about using science and technology to create beautiful and alluring artificial females who come alive.4 Again, the fantasy is an ancient one: in Ovid's telling of the myth of Pygmalion, Pygmalion creates a beautiful sculpture of a woman and falls in love with her. He prays to Venus, asking her for a real-life woman as beautiful as his sculpture, and Venus makes his sculpture come alive. Galatea, as Pygmalion named his beautiful female, is the answer to his dreams.

In Ovid's tale, Venus is the agency for transformation, but in nineteenth-, twentieth-, and twenty-first-century versions of this Pygmalion theme, men use science and technology instead. In the French novel L'Eve future (Tomorrow's Eve, or The Future Eve) (1886) by Villiers de l'Isle- Adam, a fictional version of Thomas Edison offers to help his friend Lord Ewald by creating an artificial duplicate of Lord Ewald's mistress Alicia.

The real Alicia is beautiful, but Lord Ewald is unhappy about her mediocre mind. Her new, artificial version, named Hadaly (which means “perfection” a in Persian), is a lovely, alluring, compliant being who answers to his every wish–she's an idealized (at least in Lord Ewald's terms) woman whose every response is technologically controlled, and her artful programmed responses answer to his every mood.

Hadaly is very much a product of (pseudo)science and technology: she will be fashioned through a mysterious photo-sculpting process and activated through electricity. Edison says he will use "electromagnetic power and Radiant Matter" to create her, and she will be covered with artificial flesh woven with induction wires. When the author was writing his novel during 1877-1879, the real Thomas Edison had already developed the phonograph, and stories about it had already been published in American and European newspapers and magazines. In the novel, Alicia's facial expressions and gestures were recorded on a central cylinder, and Hadaly's words were prerecorded on two golden phonographic discs that contain seven hours of language from writers, recorded by performing artists. Hadaly is presented as a technological and scientific marvel who is "better than real," giving Lord Ewald everything he desires.

Unlike Hadaly, however, the false Maria in Lang's film is an evil being representing science and technology out of control–a female version of Frankenstein's destructive creature who menaces society. In this familiar female paradigm of woman as harlot and saint, Maria, who offers comfort and hope to the workers, is transformed into a seductive vamp who dances lasciviously at the film's Yoshiwara nightclub in front of leering, tuxedoed men. She later also enflames the passions of the workers, inciting them to riot as she tells them, "Let the machines starve, you fools! Let them die!" and "Death to the machines!”–and the inter-titles tell us that the mob rushes toward the Moloch Machine, the powerhouse of Metropolis, leading to flooding, crashing, and great flashes of light.5

The evil Maria in Metropolis also suggests the darker side of the Pygmalion theme: the artificial female who brings men grief, as in E. T. A. Hoffmann's story "The Sandman" (1816), where the beautiful Olimpia causes Nathanael anguish when he discovers she is nothing more than a clockwork doll. It is also seen in Elsa Lanchester's wonderful rendition of the electrically created female in Bride of Frankenstein, who takes one look at the monster and lets out a chilling scream. In Metropolis, Freder falls in love with the saintly Maria but is horrified when he mistakes the malicious Maria for the real woman.

By the 1970s, the film industry would again be producing movies about using science and technology to create artificial women, like the women of Stepford who in the 2004 Hollywood remake of the 1975 film The Stepford Wives have been transformed through the wonders of a "female improvement machine”–from highly accomplished career women into glamorous, sexy creatures who love to cook and clean. (In L'Eve future, Hadaly is superior to the original, but in the 2004 Stepford Wives, husband Walter has misgivings and doesn't go through with the transformation process, later saying, "I didn't marry something from Radio Shack.")

The quest to use science and technology to create an artificial female so memorably portrayed in Metropolis–is still on: witness today's ultra-lifelike Japanese female robots, which look so real they can easily fool the eye. These silicone and electronic females embody our technological dreams and nightmares, as they remain alluring to many men, alarming to many women, and–in a quirky way–fascinating to us all.

Notes

1 After its initial release in Berlin in 1927, Metropolis was heavily edited by Paramount Pictures for its U.S. release the following year, and there were also other edited versions that deleted scenes and inter-titles. The film was later digitally restored and re-released in 2002. This later version included the backstory about Hel that had been edited from the film.

2 Günther Rittau, "Die Trickaufnahmen im Metropolis Film," Die Filmtechnik, 28 January 1927, translated in Thomas Elsaesser's Metropolis (London, 2000), 25. For the special effects using neon tubes, the same piece of negative was exposed up to thirty times using a black silhouette of the robot, and the scene was filmed through glass plate that was smeared with a thin layer of grease.

3 Lotte H. Eisner, Fritz Lang (1976; reprint, New York, 1986), 90.

4 For more on artificial females created through science and technology, see Julie Wosk, Alluring Androids, Robot Women, and Electronic Eves (New York, 2008), based on her museum exhibit of the same name held at the New York Hall of Science in 2007 and the Cooper Union in 2008; see also the chapter "The Electric Eve" in Wosk, Women and the Machine: Representations from the Spinning Wheel to the Electronic Age (Baltimore, 2001), and Wosk, "The 'Electric Eve': Galvanizing Women in Nineteenth- and Twentieth- Century Art and Technology," Research in Philosophy and Technology 13 (1993): 43-56.

5 In his compelling essay "The Vamp and the Machine: Technology and Sexuality in Fritz Lang's Metropolis" (New German Critique 24-25 [1981-82]: 221-37, reprinted in Andreas Huyssen, After the Great Divide: Modernism, Mass Culture, Postmodernism [Basingstoke, UK, 1988], 65-91), Andreas Huyssen argued that the evil Maria embodies men's fears of rampant female sexuality running out of control.

Julie Wosk is professor of art history, English, and studio painting at the State University of New York, Maritime College. She is the author of Alluring Androids, Robot Women, and Electronic Eves (2008), Women and the Machine: Representations from the Spinning Wheel to the Electronic Age (2001), and Breaking Frame: Technology and the Visual Arts in the Nineteenth Century (1992, with a new edition forthcoming in 2010).