Metropolis (1927).

Metropolis, Scene 103: Enno Patalas

You may remember:

"Within easy reach of the city's guiding hand stood a strange house."

"The man who lived there–Rotwang–had worked thirty years to bring true the great dream of John Masterman."

The motion picture that caused the downfall of the "old" UFA was first conceived in 1924. With Siegfrieds Tod enjoying successful runs in London and Paris, Lang visited America to study the local movie industry. He arrived from Hamburg in October 1924, accompanied by producer Erich Pommer, Felix Kallmann (President of UFA), and Frederick Wynne-Jones (the company's American representative). During their seven-week stay they visited nearly all the studios and met with many film-makers, including Ernst Lubitsch. It is said that while looking at the New York skyline from the deck of his ship, Lang thought of setting a film in such a city far in the future. He discussed this idea with his wife, Thea von Harbou, and she wrote a novel based on it, which the two then converted into a scenario.

Next you see Rotwang, the inventor, at his desk. A hunchback servant, emerging from a spiral staircase through a trapdoor in the floor, announces:

"My work is done . . . !"

"A machine that can be made to look like a man or a woman-but never tires never makes a mistake !!!"

"Now we can do without man!"

"The dream that it might be possible to go a step beyond making machines of men-by making men of machines."

"Isn't it worth the loss of a hand to have created a machine that can be made to look like a man or a woman–but never tires–never makes mistake–"1

Why does the inventor proclaim his good news with such desperate gestures and contorted expressions? A lapse on the part of the actor, Klein-Rogge? This is not the only inconsistency that will puzzle the attentive viewer of existing prints of Metropolis

If Rotwang creates a robot to replace the workers, why does he make that robot female? Even recently, an ingenious essay on "Technology and Sexuality in Fritz Lang's Metropolis" takes the motivation of this femininity for granted: "Precisely the fact that Fritz Lang does not feel the need to explain the female features of Rotwang's robot shows that a pattern, a long-standing tradition is being recycled here, a tradition which is not at all hard to detect, and in which the Maschinenmensch, more often than not, is presented as a woman.”2

The motivation of the robot's female features, as conceptualized by Thea von Harbou and Fritz Lang, remains a question that cannot be explained from existing prints, but only with the help of various documents. Metropolis has been thoroughly and irreparably destroyed, as few other films have been. On the other hand, very few films of the 1920s come with such a host of reliable and detailed source material. Thus we have the music that Gottfried Huppertz composed for the film, including not only parts of the orchestral score but also the director's cues for the pianist, together with instructions for the particular arrangement. This score contains 1,029 cues for the conductor, one for about every third bar, so as to synchronize the music with images and intertitles; the cues list almost every other shot and just about every intertitle.

In this score, the sequence which begins with the servant announcing the visitor is transcribed in the following way:

Curtain open–Fredersen close–base of monument–Fredersen–enter Rotwang–a brain like yours–only once in my life–Fredersen–let the dead rest–for me she is not dead–Rotwang's hand–do you think that the loss–would you like to see her?

Only the subsequent cues ("spiral staircase–Rotwang pulls the curtain–Fredersen–robot slowly rising") correspond to a scene of the film as we know it: after Rotwang's fierce outburst we see the inventor enter his laboratory from the staircase, accompanied by Joh Fredersen (John Masterman in the American version). They step in front of a curtain which Rotwang proceeds to open. And, as Fredersen watches tensely, the robot slowly rises and walks toward them.

In addition to the score, we a have a second document that provides reliable information, although it concerns a limited aspect of the original version of Metropolis. This is the censorship card of the Film Censorship Office in Berlin which passed the film for release on November 13, 1926 at a length of 4,189 meters. These censorship cards were actually little notebooks made out of blue cardboard–the one for Metropolis was ten pages long. In addition to credits and the length of individual reels, they contained a complete list of intertitles without, however, distinguishing between explanatory and dialogue titles or identifying speakers.

At the beginning of the third reel (of nine), the censorship card lists the following intertitles:

1. In the center of Metropolis there was a strange house, forgotten by the centuries.

2. The man who lived there was Rotwang, the inventor.

3. Joh Fredersen.

4. Hel, born to make me happy and a blessing to humanity, lost to Joh Fredersen, died when she gave birth to Freder, Joh Fredersen's son.

5. A brain like yours, Rotwang, should be able to forget . . .

6. Only once in my life, forgot: that Hel was a woman and that you were a man . . .

7. Let the dead rest, Rotwang She is dead, for you just as for me.

8. For me she is not dead, Joh Fredersen–for me she lives!

9. Do you think the loss of hand is too high a price for the recreation of Hel?!

10. Would you like to see her?!

This explains six of the cues given in the score. "A brain like yours–only once in my life–for me she is not dead" each quote the beginning of intertitles and refer to the dialogue between Rotwang and Fredersen. Intertitle 4. however–“Hel, born to make me happy”–does not have a counterpart in the score.

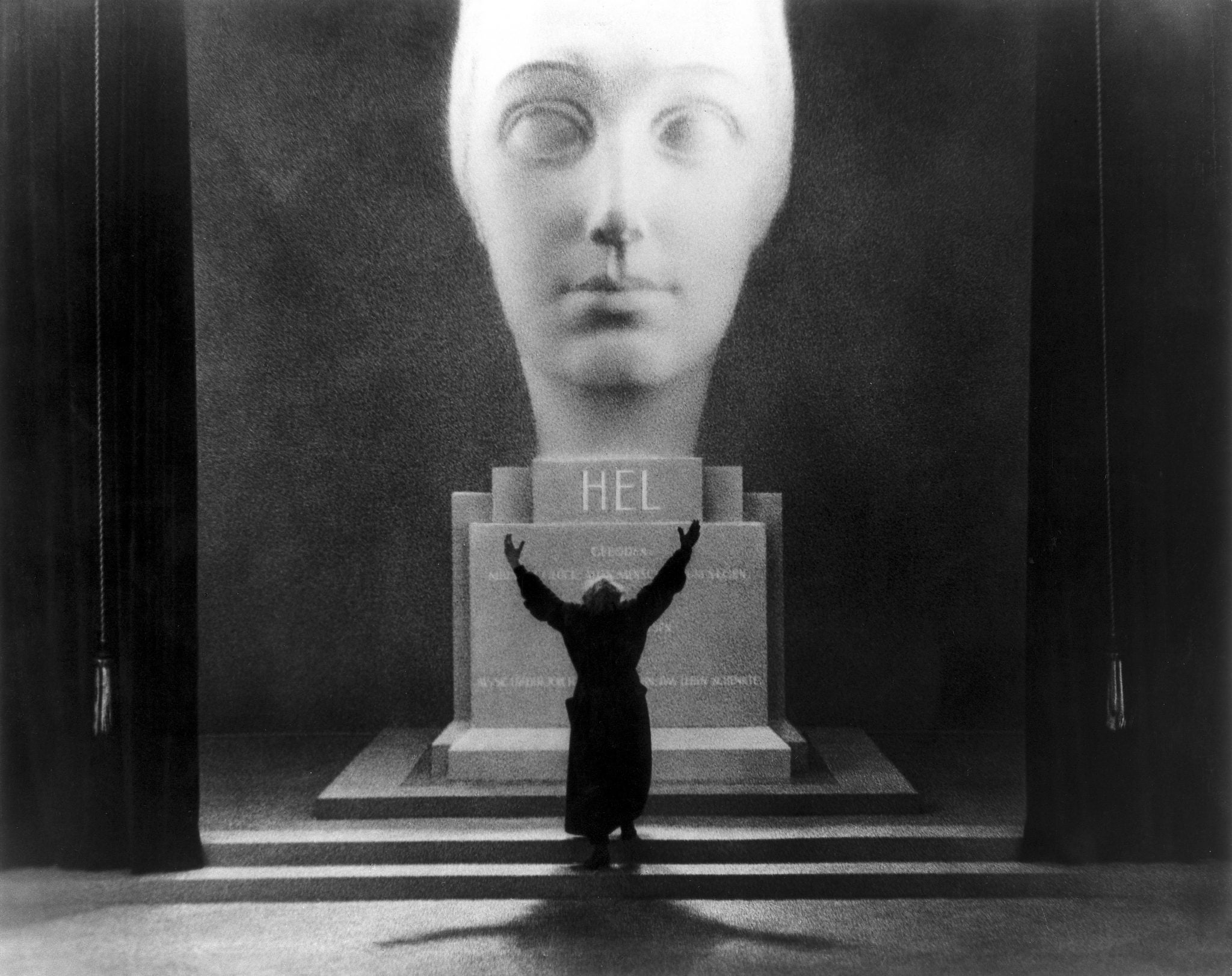

A third source sheds light on this line. In the three albums of production stills from Metropolis which Fritz Lang donated to the Cinémathèque Française in 1959, there are three photographs showing a monument, or at least its base. Flanked by Fredersen on the left and Rotwang on the right, the monument carries an inscription which we can identify as the text of intertitle four of the censorship card. Another photograph shows Rotwang raving in front of the monument, and the camera crew standing on its base. A third shows the same scene, but with a woman's head on the base–a photomontage?–and to the left and right, parts of a curtain. Now the other cues from the score fall into place as well: "Curtain open–Fredersen close–base of monument–enter Rotwang.

Finally, there is a fourth source which helps us visualize the scene. For a long time, Thea von Harbou's script was believed to be lost, until one copy surfaced in the estate of the composer Huppertz; it now belongs to the Deutsche Kinemathek in West Berlin. If we compare this script with the censorship cards, with the score, and the existing parts of the film, we find that Lang departed from the script in numerous details, that he chose to discard entire scenes, even in the original version of the film. Of Lang's shooting script, only one page has survived–as a facsimile in an UFA promotional brochure. It represents Scene 13 (Stadium of the Club of the Sons), which is missing from the American version of the film and consequently from many prints. A comparison with the corresponding pages from Harbou's script would make an interesting seminar paper.

In the script, the scene between Rotwang and Fredersen corresponds to Scene 103, entitled "Hel's Room." We could imagine the scene as follows. After the intertitle "Joh Fredersen”–the announcement by the servant–we see the person who has been announced (very often in Lang dialogue title provides the cue for the next shot) with his back to the camera, in a somber, almost empty room with high ceilings. He stands in front of a curtain that extends from ceiling to floor, "as if attracted by a magnet," according to the script; he pulls one of the curtain's heavy tassels, it opens, and behind him a monument appears with a gigantic head representing Hel. Fredersen stares, visibly moved, at the woman's head, then he reads "the words engraved on the base, which join Rotwang, Hel and Joh Fredersen in a common fate." Without a sound, Rotwang enters the room. Seeing the man who had robbed him of his beloved standing before her statue, he flies into a rage, plunges toward the monument, pulls the curtain closed behind him violently, and leans forward against Fredersen, who steps back slightly. Fredersen "becomes calmer, in the face of Rotwang's increasing rage,' and speaks (intertitle):

"A brain like yours, Rotwang, should be able to forget..."

Then follows the dialogue we know from the censorship card. Rotwang:

"Only once in my life, I forgot: that Hel was a woman and that you were a man. Fredersen, gentler than usual: "Let the dead rest, Rotwang... She is dead, for you just as for me...

" Rotwang, in mad triumph: "For me she is not dead, Joh Fredersen–for me she lives!" And so on.

It is well known that Metropolis was produced by UFA under the terms of the Parufamet agreement of 1926. Paramount-Famous Players-Lasky and Metro-Goldwyn supplied a loan of 17 million marks in return for which UFA agreed to distribute forty Paramount and MGM films and to allocate to them half of the exhibition time available in UFA theaters. The American companies, for their part, agreed to distribute ten UFA films in the United States.

The Berlin premiere of Metropolis took place on January 10, 1927. At this point, an American version was already being prepared. On March 13, The New York Times published an article with the title "German Film Revision Upheld as Needed Here," in which a certain Randolph Bartlett justified the cuts and changes made for the American release.3 The Germans' problem was either a "lack of interest in dramatic verity or an astonishing ineptitude. Motives were absent or were extremely naive." This could not be tolerated.

The German producers were quick to accept the American verdict. As early as April 7, the UFA Board of Directors resolved to persuade Parufamet to release Metropolis in the provinces in the fall, and to re-release it in Berlin at the same time, "in the American version4 after deleting as many intertitles as possible with a communist tendency.”5 The next day the distributor suggested withdrawing the film, and releasing the new version at the end of August, in Berlin first, after some of the "pietistic revisions6 added by the Americans were removed." The UFA Board of Directors complied on April 27, and by August 5, the film was resubmitted to the Censorship Office in a version 3,241 meters long, in other words, cut by nearly a quarter. About half of approximately 200 original intertitles survived, more or less exactly, the other half were dropped; 50 new intertitles were added.

The cuts in the American and the second German version are largely the same, although the Americans cut 400 meters more than the Germans. They also took more liberties with reediting and intertitles. The formulation of new titles went hand in hand with a new montage that both shortened and rearranged the film, even breaking into individual sequences. Thus, changing the dialogue between Rotwang and Fredersen in Hel's Room into a monologue by Rotwang on the creation of the robot rendered all shots superfluous in which Fredersen is seen speaking. These shots were either eliminated or, as in the case of one shot, inserted at another point in the film, so as to give Fredersen a chance to remark about the robot: “It has everything but a soul.”

Why the monument of Hel and thus the character of Hel and the motivation for Rotwang's behavior had to be sacrificed to the American censors, we learn from The New York Times:

[The scene] showed a very beautiful statue of a woman's head, and on the base was her name--and that name was "Hel." Now the German word for "hell" is "Hölle," so they were quiet [sic] innocent of the fact that this name would create a guffaw in an English-speaking country. So it was necessary to cut this beautiful bit out of the picture, and a certain motive which it represented had to be replaced by another.

For Harbou and Lang, Rotwang's story was, as the song goes in Rancho Notorious, "a story of Hate, Murder and Revenge," with a complex motivation. In the amputated version of Metropolis, Rotwang, the genius inventor, is little more than a tool in the hands of Fredersen, at whose command he instructs the robot to instigate a self-destructive revolt among the workers. For Harbou and Lang, Rotwang had his own reasons for creating the robot as the "new Hel."

The women in Metropolis are the projections of male fantasies, authorized by Rotwang, Fredersen, and Lang–the spectator in front of the screen recognizes himself among the spectators on the screen: in Freder, when the door to the Eternal Gardens opens and Maria, the virgin-madonna, appears surrounded by the children; in Fredersen, when Rotwang pulls open the curtain and the new Hel, the robot, arises; in the collective of men in tuxedos at Rotwang's party, as the new Hel, flesh incarnate, appears on a broad dish emerging from beneath the stage, her position fixed until she begins her dance. Invariably, the woman, virgin, mother, whore, witch, vamp7 is constituted–and de-constituted–under the direction of one of the male characters, which in turn predicates the look of another, or many others, including the spectator. And Lang also presents these looks, in the "thousand eyes" of the spectator at Rotwang's party.

Rotwang presents Hel as a stone monument. As he had chiselled into stone, she "was born for him." She had refused him by marrying another for whose son she died-a son who should have been his, according to the law of her birth. He built a monument to her in his house and concealed it behind a curtain, as if he didn't want to share his grief with anyone, to keep the dead woman to himself. But his way of presenting Hel is also clearly motivated. Hel had to be born, had to betray him and die, so that Rotwang could turn her into a stone monument.

In this retrospective conception, Hel prefigures the new, artificial woman as her double. She would not merely be "born for him"; she would be born "of him”–daughter and lover in one. He gives this artificial woman the features of the girl with whom the dead woman's son has fallen in love, so as to have him be destroyed by her double. Thus he takes his revenge not only on his rival, but also on the son who denied himself to Rotwang when his mother conceived him by another. He fantasizes the desired son as the offspring of his lover's infidelity which in turn allows him to motivate and rationalize his sadistic lust.

The authors of the American version were not as naive as they pretended to be when they eliminated Hel. Their stale joke about "this a hell of a woman" gives them away.

Translated by Miriam Hansen

Editors' note: This translation from the German appears by permission of the author. The article was originally published in French translation in Metropolis, un film de Fritz Lang: Images d'un Tournage (Paris: Centre National de la Photographie et Cinémathèque Française, 1985). We would like to thank Enno Patalas and Gerhard Ullmann of the Munich Film Archive, and the Cinémathèque Française for the photographs used in this article. Enno Patalas has been responsible for the major part of the reconstruction of Metropolis. The version released by Giorgio Moroder in 1984 owes a great deal to this archival work. The sub-plot involving Hel would be known to readers who have seen Moroder's print; this, and several other "lost" scenes, were included through an inventive use of photographs and optical effects.

Notes

1 Titles are from the American release version.

2 Andreas Huyssen, "The Vamp and the Machine: Technology and Sexuality in Fritz Lang's Metropolis,' New German Critique 24–25 (Fall/ Winter 1981–82), p.225.

3 Quoted in Paul M. Jensen, The Cinema of Fritz Lang (New York: A.S. Barnes, 1969), p.64.

4 Transcripts of the UFA Board of Directors meetings, Bundesarchiv, Koblenz.

5 The intertitles of Maria's inflammatory speech to the workers survived, almost literally, in the American version. They were toned down only in the second German version.

6 The American version added a number of interpretive intertitles and even completely new dialogue. Thus Freder (now called Eric) says to Joh Fredersen (now John Masterman): "Father, for centuries we've been building a Civilization of Gold and Steel – what has it brought us? Peace? Understanding? Happiness? Has it brought us nearer to God?…”

7 On the etymology of the name Hel – in the Old German Edda, the ruler of the underworld, the Goddess of Death – see Georges Sturm, "Für Hel ein Denkmal, kein Platz-un 'rêve de pierre'," cicim 9 (Munich, 1984). 9