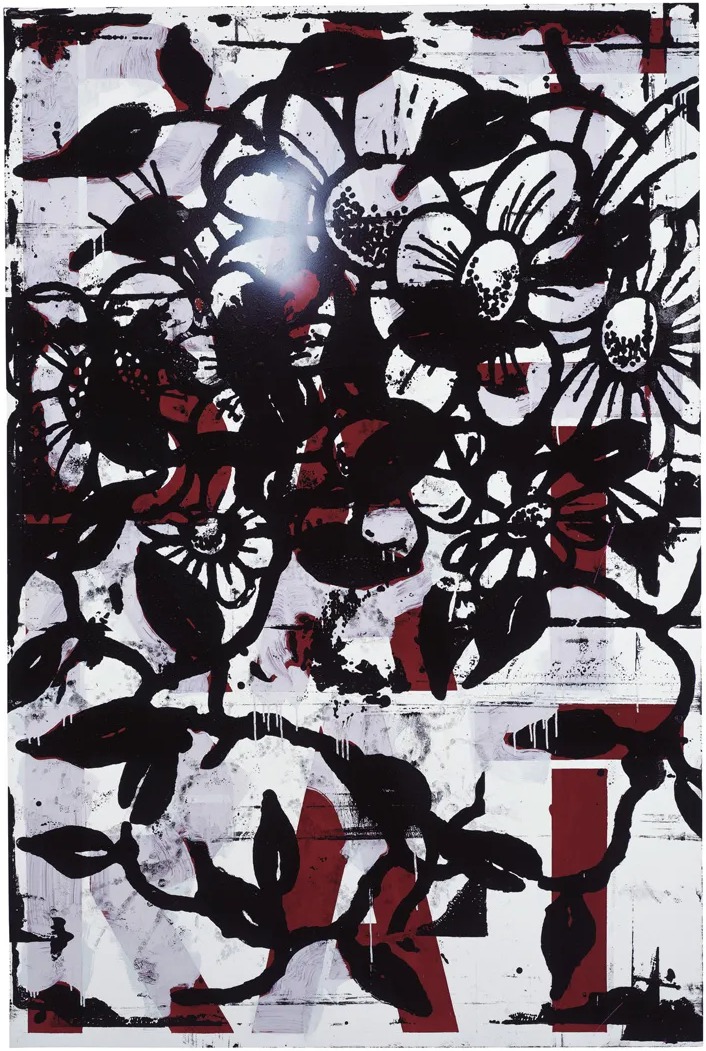

Christopher Wool, I Smell A Rat. 1989–94

Christopher Wool: Marga Paz

What is needed, for painting to exist, is not simply that the painter should take up his brushes. He also has to manage to show us that we could definitely not do without painting, that it is indispensable for us, and that it would be madness—or even worse, a historical error—to let it lie uncultivated. That means finding a new raison d’être for it, as others succeeded in doing in the past for the invention of perspective.” – Hubert Damisch

Reflections on painting

This quotation, taken from Fenétre jaune cadmium, the collection of essays written between 1958 and 1984 by Hubert Damisch,1 gives us the keys to what painting should be in order to have relevance as a medium of art in the 21st century, in order to be considered as possessing sufficient vitality of its own and therefore not reduced to a mere repetition of empty signs, irremediably unsuited to their time.

Thus the painters who, despite differences in style and sensibility, manage to make us believe once again in their validity, aware that they live in the age after the—much heralded but no more valid for all that—death of painting, are the ones who initially set out from the assumption of the fictitious relationship that any art has with its own time, and who go on to create new circumstances that make the survival and relevance of the genre as such possible.

In this context, Christopher Wool’s work must be considered one of the most radical, innovative and therefore important reflections of pictorial thinking of the present time. We are confronted with work that deals with the possibilities and mechanisms that keep painting alive and valid in the present, an issue that, despite all forecasts, is one of the most productive and complex issues in contemporary visual art.

Ever since the invention, in the mid-19th century, of photography, which took over some of painting's functions and thus called it into question as a genre, it is precisely this potential end of the practice of painting that has given rise to one of the longest debates—and also, sometimes, one of the most sterile from a theoretical viewpoint.

We must also say that the tensions generated have proved most fruitful, if we consider much of what has been produced, and if we also take into account the renewed interest that painting has continued to arouse periodically ever since the rupture in practice and conception that the 20th-century avant-garde movements signified in their day, continuing to the present time despite the fact that this is an age in which we live under the rigid dictatorship of an image-based culture that predominates in every aspect of contemporary life. And this may be one of the very reasons why painting is still a redoubt for individual practice and experience, free of the impositions of immediacy, yet remaining in constant conflict with them.

All these issues were reflected from the outset in the work of this American artist, born in 1955, who came to public attention in the late eighties. It was in that decade, after the abandonment of painting by much of the art of the sixties and seventies, that there was a resurrection, yet one based on an “utterly reactionary rhetoric’, discussed by Douglas Crimp,2 to which some artists thought they could react by using painting, but from a radically opposite viewpoint.

It was in this context that Wool attracted great attention in the late eighties, with paintings done solely in black and white, some with ornamental motifs and others with fragments of text but all with a strong visual impact. “Wool’s work has followed a trajectory that is at once historically reflexive, very much of its own moment, and keenly self-critical. Wool’s work has drawn from a variety of experiences both inside and outside art, with a frame-work that is concerned with the history, conventions and problematics of making a painting in the 1980s and 90s—his work embodies and encourages its own contradictions.”3

From the beginning his basic interest resided in reconsidering the image, as is clearly reflected in his pictorial language, which is a result of juxtaposing various visual and conceptual discourses from an impersonal, critical viewpoint that can clearly be considered as deriving from Pop Art, showing an interest in pre-existing motifs taken from the consumer society and in specific techniques of the mechanical reproduction of images.

It is not surprising, therefore, that his early works borrowed various features from the milieu of mass production, with their use of industrial materials, procedures and techniques (aluminium, silkscreen, varnish, photography, paint rollers, stencils, etc.) and an iconography reduced to fragments of text or else organic forms used as decorative motifs.

Word paintings

In his word paintings, the whole surface is covered with words, phrases and even jokes and curses, such as “RIOT”, “PRANKSTER’, “FOOL”, “BAD DOG”, “RUN DOG RUN’, “PLEASE PLEASE PLEASE PLEASE PLEASE” and, most recently, “THE HARDER YOU LOOK THE HARDER YOU LOOK” (2001), taken from a variety of sources and from other media, such as music, films and popular culture.

One of the best known phrases is “SELL THE HOUSE SELL THE CAR SELL THE KIDS”, words written—expressing a definitive break, with no possible return—in one of the scenes in Francis Ford Coppola's film Apocalypse Now, which is also the title of this work painted in 1988.

This series, begun in 1987, consisted of paintings on a white ground, on aluminium surfaces, with prominent black capital letters, painted with stencils and set side by side with no connecting punctuation, which made them sometimes mysteriously hermetic and incomprehensible, sometimes ironic, sometimes distressed or critical, but always elusive when it came to revealing a meaning that was not uncertain.

At that point they were associated with the milieu of the rough punk poetics of the time, as a subtle postmodern fusion of black humour and concrete poetry, effectively exploring a key area of our most recent cultural history.

But they were also interpreted by some as an attempt to illustrate the limitations, if not the difficulty, of the communication of language and the impossibility of a symbolic significance. By using the word also in its capacity of visual material, leading to obscuring the legibility of the texts by accommodating them primarily to the impositions of the picture space, Wool made the viewer reinterpret the meaning of the words used in his paintings, thereby underlining the failure of language as an effective, objective medium of communication.

Ornamental motif paintings

In 1986 he began to produce another group of works which defined his output in the early stages of his career: the first paintings with floral motifs, done with a roller on painted aluminium, making impressions derived from ornamental models of flowers and vine shoots which belonged to the realm of a nature created artificially for wallpaper patterns: flowers, vegetation or birds, arranged in sequences.

Although they came from the world of ornamentation, these motifs were stripped of any decorative, symbolic or descriptive quality, unlike what had been done by the “pattern painting” of the seventies, which emphasized the decorative aspects that Modernism had set out to discredit. Ornamentation had similarly been eliminated from the language of modern architecture by the functionalism preached by Adolf Loos in his famous essay “Ornament and Crime” (1908), where the celebrated architect declared that ornamentation should be associated with a particular historical style.

With Andy Warhol’s Flowers series (1967) as a specific precedent, these works by Wool consciously choose an anonymous, banal iconography which was already out of fashion when he used it, so that, as Bruce W. Ferguson says, “he stamped paintings also appear iconic or symbolic, but the icon or symbol presented is so vague and generic that, upon scrutiny, it immediately withdraws from specific meaning. It’s not simply that the works of Modernism could be absorbed as decoration, these slightly smeared paintings seem to say, but also that any attempt to go beyond the surface—to transcend the specific—is accompanied by foreboding.”4

The affinities with Warhol are more extensive, as both series are constructed by repeating a printed flower image on a monochrome background using industrial painting techniques, with an iconography that belongs to mass culture. This is one of the ways in which Wool accepted and revised the legacy of Pop Art, as did the greater part of the most interesting art produced in the eighties.

Wool also made use of repeated elements in these compositions, like some of the other artists of his generation, especially those who used photography in their work, such as Richard Prince.

But even before that, in the late seventies and the eighties, movements with very different aims, such as Pop Art and Minimalism, had coincided in using serial production, in an attempt to work against the traditional notions of artistic composition.

From the early nineties onwards, these floral motifs were silkscreen printed and enlarged and repeated so that they expanded over the surface of the painting, sometimes occupying it almost entirely, in overlapping layers that sometimes created a stifling space in which the chaos caused by the intervention of chance and the accidents brought about by the various production processes were clearly visible, as Anne Pontégnie indicates: “Starting in 1995, the structured compositions of the paintings, already destabilized by the accumulations of layers, gradually gave way to an increasingly dense and complex entanglement. Motifs of various origins, painted or silk-screened, were copied, repeated, and superimposed. The expression and pictorialism shifted from accident toward hesitation and repentance, from the margins to the center. Sometimes, wide bands applied with a roller blocked the composition as though to hide uncontrolled bursts of spontaneity.”5

Origins

Although he grew up in Chicago, his artistic career has been linked personally and artistically with the city of New York, where he currently lives, having moved there in the early seventies. It is in that city that we must look for Christopher Wool’s artistic origins, connected with the influence on the art world wielded by the energy of counterculture and the radical attitudes of the punk scene, which made a substantial impact on him and left traces still visible in his works today.

There are marked differences between the various artists who began to become known on the New York art scene in the early eighties—some of them born, like him, around 1955—but all those artists shared a marked interest in open confrontations between highbrow and lowbrow culture. This led them to take an interest in various aspects of mass culture in films, television, advertising or music, which in one way or another were absorbed into their works. They included Cady Noland and Philip Taaffe, among others; and also Jeff Koons, who worked on the transformation of sculpture into consumer goods; and Robert Gober, who used the fragmented body to treat the theme of sexuality and death; while others, such as Richard Prince or Cindy Sherman, called the photographic image into question.

Yet the critical, subversive activity underlying their works marked an irrevocable difference with regard to the representatives of the new Neo-Expressionist painters of the eighties, who used motifs and techniques from different milieus indiscriminately, but in order to restore the traditional values of painting, as in the case of Julian Schnabel. “Wool’s work,” says Madeleine Grynsztejn, “shares Pop art's affection for the vulgar and the vernacular, and in form it recalls Pop’s graphic economy of means, iconic images, and depersonalized mechanical registration.”6

Reality and its representation

At that point there was a shift in the work of those artists, in which reality was replaced by its representation. No doubt this helped to direct Wool towards the use of iconic images and depersonalized, mechanized inscriptions in his paintings, produced with an economy of means that owes much to Pop Art, many of the artistic concepts of which also form the basis of the work of all the artists of his generation.

In Wool this influence takes place in a personal, individual way, as shown by his particular use of reproduction as a way of treating images and his interest in icons of urban culture. It is also revealed by his very interesting but not very well-known black and white photographs, which he has been producing since the eighties, including: Absent Without Leave, taken during the period he spent in Berlin and Rome and the journeys that he made at that time in Turkey and Europe; Incident on 9th Street, a collection of black and white photographs of the damage caused by a fire that burnt down his studio; and East Broadway Breakdown, 1994–95, a series in which he collected signs of the urban landscape, obtained in the darkness of the night in the streets of New York City.

In his current work he modifies the postmodern concept of the “replica”, questioning the real difference between original and reproduction, rather like what Warhol did in his 1974 Reversals series by using photographic reproductions of his earlier works, which reappeared as silkscreen prints, sometimes in the form of fragments with deliberate alterations of scale, thus transforming their intrinsic quality of being an original work of art.

In the catalogue for his 1991 exhibition Cats In Bag Bags In River at the Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen in Rotterdam he reproduced his paintings as colour photocopies, printed with the distortions that took place during the process of reproduction and the accidents resulting from the intervention of chance. He had also begun to take Polaroids of the different states through which his paintings passed, sometimes using them later and working directly on the photographs.

Thus, in various stages and in different ways, Wool has intuitively developed a reappropriation of his own works, which act as a background on which—by superimposing a series of layers—he constructs an abstraction that looks gestural and eminently pictorial but is really a way of demolishing Abstract Expressionism’s concept of pictorial expressiveness.

Codes and techniques

Christopher Wool carries out various operations concerned with repeatedly revising pictorial codes, putting them in a state of crisis by means of actions which he performs simultaneously and which bring about the complex visual interferences that shape his works: diluting the strict boundaries between the roles played by abstract and figurative elements, working in series, transferring the impersonality of the procedures of conceptual art to his paintings, painting on a variety of materials such as aluminium, accepting the accidents that occur during the making of the picture, using serially produced images taken from the world of industry, and contrasting items of different origins, some derived from his earlier works.

One has the sensation that the complexity which plays an essential part in the composition of the work seeks to make up for a persistent, deliberate restriction of colour by extending towards a field open to a combination of a heterogeneous series of varied techniques and materials—such as the use of enamel, spray paint, silkscreen, paint roller, etc.—which produce a mingling and a mutual interference between manual painting techniques and mechanical means of reproduction such as silkscreen.

Making and unmaking

This confrontation is deliberately used to produce particular results, which are also generally enhanced by the employment of tactics that set out to cancel and correct earlier elements. These devices involve the use of actions such as erasing, covering, removing, hiding, staining and so on, with which Wool gave a radical twist to his way of working at a certain point, initiating a change directed towards producing the picture by means of processes of destruction used as a method for his personal process of construction.

It was in 1997 that Wool made this substantial turnabout in the concept of the construction of his paintings, taking them towards the possibility that the action of erasing could be a privileged method of production. To do this he superimposed layers of white on silkscreen models that had been used in previous works, converting the operation into a specific kind of erasure intended to leave its traces on the picture plane. Another form of erasure consisted in using spray paint to go over the traces left by the lines that he had made, giving the appearance of graffiti.

This, in turn, has led to the onset of a kind of creative operation that spans the whole spectrum of negative and positive in his painting. In other words, the opposite actions of adding and suppressing entwine and produce mutual interference, while his painting also works on contrasting concepts such as depth and surface or abstraction and figuration, leading to the presence of a permanent instability induced by the resounding rejection of any attachment to specific artistic styles or ideologies that has always characterized his work.

There is no doubt that inherent in the very nature of these creative processes there is an element of destruction that is always apparent in his work, for the process of negation of each participating item that takes place in the picture is also a productive element connected with the impossibility of communication with language, as revealed in the word paintings at the start of his career.

Gesture and process

Although Wool still uses mechanical means such as silkscreen as a way of constructing many of his paintings in his most recent output, a broad sample of which can be seen in this exhibition, one could say that in most of his works there is an operation of going back to painting techniques that were part and parcel of Abstract Expressionism, based on the gestural manner in which brush strokes were applied to the canvas, a characteristic feature of De Kooning’s work.

It is not surprising that this movement—the first great movement of American painting which sought to present itself as a starting point that would provide a foundation, establishing a direct relationship with the beginnings of abstraction without intermediaries—should serve as an essential reference point in current attempts to create a new abstraction, which sets out to effect an immersion in the reality of painting itself through experience and action.

One of the first influences that Wool experienced was the concepts of “process art”. This helped him to form his own notion of process, which he went on to apply to his painting practice. Abstract Expressionism had already sensed that this concept could constitute an extraordinary focus, and Post-Minimal artists later sought to use it to oppose the established conventions of painting and sculpture; they also reacted against Abstract Expressionism, stripping artistic experience of subjectivity and directing it towards the industrial conditions of contemporary society, especially the works in which Richard Serra threw liquid lead on the floor, thus converting the process into the art object.

Gesture made its appearance in Wool’s career in 1998. He had previously experimented with it on paper, and it became increasingly frequent as he drew brushstrokes that attempted to fix movement in the picture space, the temporal quality of which is precisely that of arresting time and remaining in a present continuum, appreciating the indifference to time that is shown by the very nature of the pictorial image and is one of its main characteristics, as Siri Hustvedt says in the introduction to her collection of essays Mysteries of the Rectangle: “I love painting because in its immutable stillness it seems to exist outside time in a way no other art can. The longer I live the more I would like to put the world in suspension and grip the present before it’s eaten by the next second and becomes the past. A painting creates an illusion of an eternal present, a place where my eyes can rest as if the clock has magically stopped ticking.”7

Yet Wool’s most recent work, with strategies that distance it from the heroic rhetoric typical of Expressionist gesture, makes a cool, premeditated review of those pictorial conventions as a conceptual model on which to construct contemporary abstract painting, yet without allowing this approach to imply a continuation of history or dependence on it, and also without lapsing into the mere use of quotations and even formal parodies so often employed in many other modern works, which thereby run the risk of making abstract language academic.

Colour

It is only since 1998, after his retrospective at MOCA Los Angeles, and then only on a few occasions, that his work has shown a more extensive use of colour not limited exclusively to the black and white of his early works and much of his current output or to the presence of a single colour—red, yellow or pink standing out against the background. Wool still maintains a deliberate restriction in the colour register of his palette, which basically varies between white, the black with which Franz Kline constructed his powerful pictorial structures, and a rich, heterogeneous range of greys produced by interrelationships between those two colours.

The vibrant colour fields with subtle nuances which dominate his most recent works have thus taken the place that was previously entirely given over to an abrupt reduction of the colour range and to the contrasts presented in his practically monochrome abstract compositions.

Resistance

Christopher Wool works on the crisis on which the painting of our time is definitively based, and he responds to it by demonstrating a special capacity of resistance that may sometimes prove disconcerting, not always well received by those who are now excessively accustomed to the immediate satisfaction of their consumer desires, a satisfaction often subject to the trends and impositions of a competitive art system.

The same obstinacy has led him to buck the trend, restricting the variety of his palette and the elements that make up his paintings. Wool deliberately confines himself to a self-regulated economy of means which lies at the opposite extreme to the voracious desire for constant innovation that dominates the art of the present time, even when that novelty does not set out to be more than a parody of what has already been seen.

His current work shows that he is still exploring the problems that affect him, some of them already present at the outset of his career. His artistic concerns are grounded in them, based on a constant examination of the limits of painting which is created, in his case, by the very action of painting, thus offering the viewer the unique experience of confronting the actual materiality of painting every time that he stands before one of his pictures.

Notes

1 Damisch, Hubert: Fenétre jaune cadmium ou le dessous de la peinture. Seuil, Paris 1984, p. 293.

2 Crimp, Douglas: On the Museum's Ruins. The MIT Press, Cambridge (Massachusetts) — London 1993, p. 90.

3 Goldstein, Ann: “What they’re not: the paintings of Christopher Wool”, in Christopher Wool. The Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles 1998, p. 256.

4 Ferguson, Bruce W.: “Patterns of Intent”. Artforum, September 1991, P. 97.

5 Pontégnie, Anne: “Chien fantéme’, in Christopher Wool, Crosstown Crosstown. Le Consortium, Dijon 2002, p. 13.

6 Grynsztejn, Madeleine: “Unfinished Business”, in Christopher Wool. The Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles 1998, p. 266.

7 Hustvedt, Siri: Mysteries of the Rectangle. Essays on Painting. Princeton Architectural Press, New York 2005, p. XV.