The viewer vis-à-vis the interior perspective views of Mies van der Rohe: Marianna Charitonidou

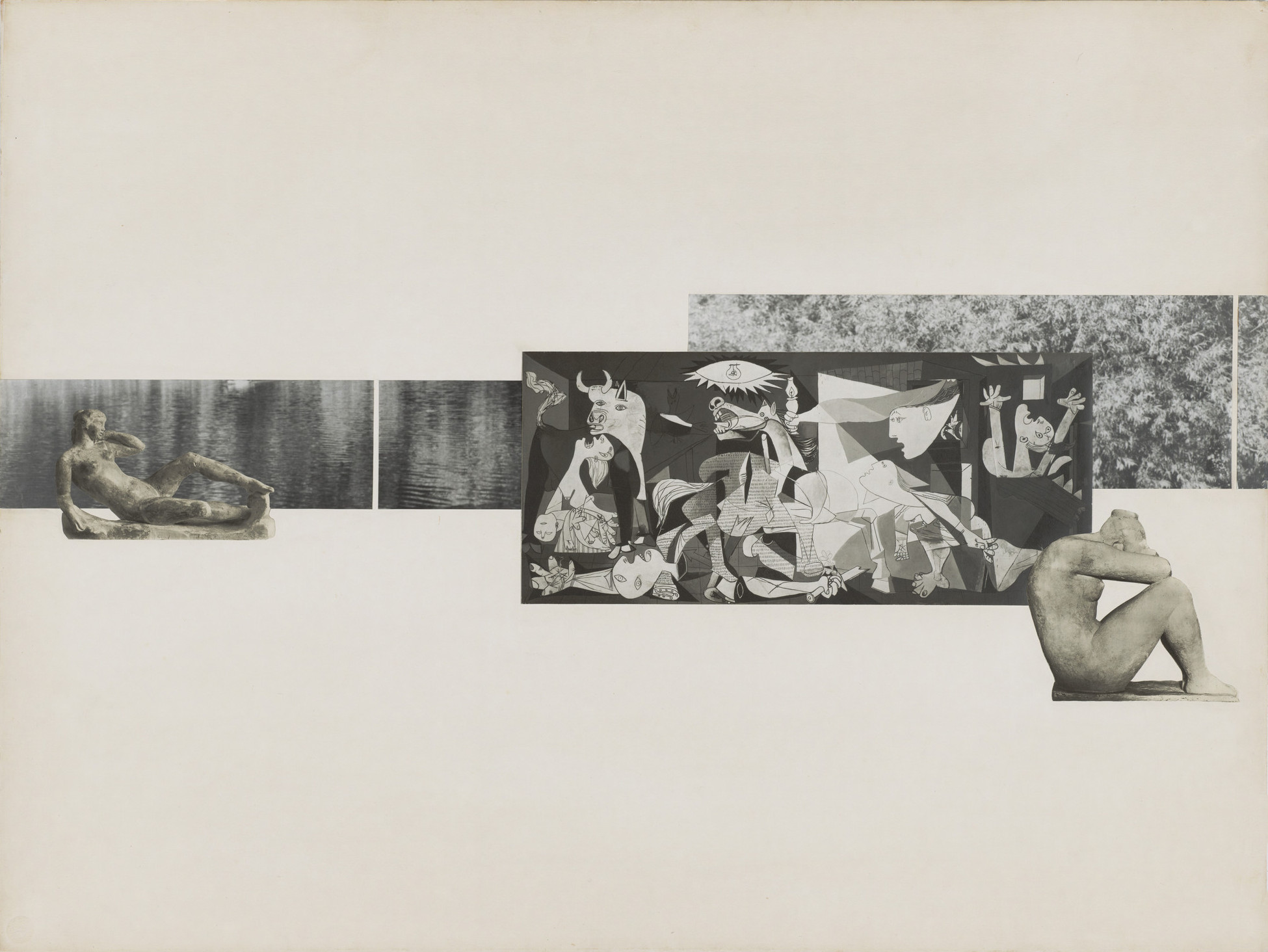

1. Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, Museum for a Small City project (Interior perspective) (76.13 x 101.5 cm) 1941-43,

Mies van der Rohe tended to work on his ideas mainly through sketches of plans and interior perspective views, as in the case of the Gericke House (1932). For this project, he also drew several aerial perspective views. The Gericke House and the Hubbe House are European residential projects of Mies van der Rohe that were not built. Mies van der Rohe, during the design process, used very often the points of the grid as guides. This permitted him capture a rhythm and imagine how movement in space would be orchestrated. In his drawings, the stairs play a major role, as in the case of the round stairs of the Resor House project. Vanishing points represent points in space at an infinite distance from the eye where all lines meet. Perspective drawing in the West uses either one central vanishing point, two vanishing points to the left and the right or, occasionally, three vanishing points, with the third being zenithal. The vanishing point and the eye are symmetrically opposed. In other words, the vanishing point is the eyes counterpart.

In Mies van der Rohe's interior perspective views for the Museum for a Small City project, which were produced between 1941 and 1943, the horizon line is placed at the mid-height of the illustration board and the vanishing point is placed at the center. The distance of the horizon line from the ground is the one third of the height of the represented space. The height of the standing statue is almost as the midheight of the space. If we take as reference the dimension of Guernica and if we make the hypothesis that the cut-and-pasted reproductions of artworks are at the right scale, we can assume the height of the space. The dimensions of Guernica are 3.49 x 7.77 m., that is to say that the height of the space is almost 3.5 m. and the horizon line is placed somewhere between 1.4 and 1.6 m (Figure 1). The strategies that Mies van der Rohe used while producing his interior perspective views push the observer to focus on the horizon line. The line of the horizon is identical to the horizon line used to construct the perspective. Nicholas Temple maintains, in Disclosing Horizons: Architecture, Perspective and Redemptive Space, that "[t]he notion of horizon [...] served as the visual armature around which modern constructs of universal space were articulated”[1].

We could relate the height of the actual horizon to the real dimension of architecture and the height of the horizon line used to fabricate the image to the fictive dimension of architecture. This means that, in the case of several of the interior perspective views of Mies van der Rohe, the real and the fictive dimension of architecture coincide. The apparent horizon, which is called also visible horizon or local horizon, refers to the boundary between the sky and the ground surface as viewed from any given point. A different definition of the visible horizon could be the following: a horizontal plane passing through a point of vision. The visible horizon approximates the true horizon only when the point of vision is very close to the ground surface. The horizon used to construct the perspective view is also called vanishing line. Therefore, we have three horizons: the visible horizon, the real horizon and the vanishing line. The horizon is always straight ahead at eye level.

A main implication of the conventional use of perspective is the establishment of a fixed view. We could argue that Mies van der Rohe, in opposition to this implication of perspective, aims to perturb this fixation. This confusion of fixation is provoked due to the way he constructs his interior perspectives, which pushes the viewers of his representations to perceive as equivalent “the ground and the ceiling planes about a horizontal line at eye height”[2]. The line of the horizon is the same as the pictures horizon line. This provokes a confusion of the viewer's perception of spatial and structural elements. The viewer's position within the space is such that the horizon line (eye height) is half the height of the interior. The horizon line (imaginary) coincides with the horizon (actual). Evans related this effect to that experienced by people when they try to see something far away[3].

The effect of equivalence of floor and ceiling planes locks the view of the observer onto the horizon line. In parallel, this visualization strategy directs the view of the observer outwards, towards the horizon and deep space, where all views vanish. In other words, the visual dispositifs that Mies van der Rohe fabricated and his way of establishing a horizon exploiting the confusion between the actual and imaginary horizon, orientate and direct the spectators’s view in depth and towards outside. The result is that the spectators are treated in a way that obliges them to construct mentally the image of the real horizon. These tricks that Mies van der Rohe used sharpen spectators’s perception, pushing them to view landscape through the opening in a way that reminds the way we view landscape when we take photographs. The architectural frame invents a horizon and hence a world that it masters through its interiorizing devices. Robin Evans has underscored that in the case of Mies van der Rohe's perceptive drawings for the Barcelona Pavilion “[t]he horizon line became prominent”[4]. As Fritz Neumeyer suggests, “[i]n the Barcelona Pavilion, Mies demonstrated brilliantly the extent to which the observer had become an element of the spatial construction of the building itself.”[5]

Another distinctive characteristic of the interior perspective views of Mies van der Rohe that should be analyzed is the use of grid. The grid serves to accentuate the distance between the artworks, the columns and the walls, in the case that these (the columns) exist. August Schmarsow notes, in “the essence of architectural creation": Only when the axis of depth is fairly extensive will the shelter [...] grow into a living space in which we do not feel trapped but freely choose to stay and live”[6]. The grid represented on the floor of many interior perspectives of Mies, as in the case of the interior perspective views for the Court house projects (c.1934 and c.1938) and of the two interior perspective views for the Museum for a Small City project (1941-43), which combine collage and linear perspective and have grid on the floor, intensifies the effect of depth in the perception of the observers of the drawings. The space is represented as tending to extended on the axis of depth and on the horizontal axis. We could argue, drawing upon Schmarsow's theory, that the sensation of extension provoked by the use of grid and the use of non-framed perspective view gives to the spectator a feeling of freedom. The use of grid and the dispersed placement of artworks and surfaces on it serve to intensify the sense of spatial extension in the perception of the observers of Mies van der Rohe's architectural drawings.

Certain images and spaces of Mies van der Rohe provoke a deterritorialization in the perception of the observers of the drawings or the users of the buildings. This phenomenon of deterritorialization is intensified by Mies's minimal expression. In many cases, for instance, the lines of the spatial arrangements are less visible than the objects, the artworks and the statues represented in his architectural representations. This strategy pushes the observers of Mies's photo-collages to imagine their movement through space. This effect is reinforced by the simultaneous use of perspective and montage in the production of the same architectural representation. This tactic invites the observers of the images to reconstruct in their mind the assemblage of the space, facilitating, in this way, the operation of reterritorialization, which follows the phenomenon of deterritorialization. In this way, the process of reconstruction of the image provokes a perceptual clarity and an instant enlightenment.

Two aspects of Mies van der Rohe's representations that are note-worthy are the frontality and the stratification of the parallel surfaces he often chose to include in his representations. The choice of Mies to use the stratification of parallel surfaces as a mechanism of production of spatial qualities in combination with the frontality of his representations could be interpreted through August Schmarsow's approach. Schmarsow defined architecture as a “creatrix of space" (“Raumgestalterin”). He was interested in the notions of symmetry, proportion and rhythm. In his inaugural lecture entitled "The Essence of Architectural Creation” (“Das Wesen der architektonischen Schôpfung”)[7], given in Leipzig in 1893, he presented “a new concept of space based on perceptual dynamics”[8]. It would be interesting to try to discern the differences between a conception of space based on Schmarsow’s approach and a conception of space based on phenomenal transparency, as theorized by Colin Rowe and Robert Slutzky in "Transparency: Literal and Phenomenal”[9].

August Schmarsow, in Das Wesen der architektonischen Schoepfung, originally published in 1894, aimed to establish a scientific approach to art ('Kunstwissenschaft) based on the concept of space. His main intention was to discern "the universal laws governing artistic formation and stylistic evolution”[10], Schmarsow conceived architecture as a “creatress of space”[11]. He used the term "Raumgestalterin" to describe the inherent potential of architecture to create space. A distinction that he drew is that between the sense of space, which he called "Raumgefühl", and the spatial imagination, which he called "Raumphantasie". The concepts of “Raumgestalterin”, "Raumgefühl" and “Raumphantasie” could elucidate the ways in which we can interpret the relationship between the conceiver-architect and the observer of architectural drawings, as well as the relationship between the interpretation of architectural representations and the experience of inhabiting architectural artefacts.

Towards a conclusion: Mies van der Rohe's representations as symbolic montage

Mies van der Rohe used perspective as his main visualizing tool against the declared preference of De Stijl, El Lissitzky and Bauhaus's for axonometric representation. Many of his perspective drawings were based on the distortion of certain conventions of perspective. In order to grasp how his drawing techniques shaped the way the interpreters of his drawings viewed them, it is important to discern and analyze what are the exact effects produced by the overcoming of the conventions of perspective by Mies. An important role in his endeavor to challenge the conventions of perspective played the use of the technique of collage or montage. In an interview, he gave to six students of the School of Design of North Carolina State College, in 1952, Mies van der Rohe remarked:

People think with the open plan we can do everything — but that is not the fact. It is merely another conception of space. The problem of space will limit your solutions. Chaos is not space. Often, I have observed my students who act as though you can take the free-standing wall out of your pocket and throw it anywhere. That is not the solution to space. That would not be space[12].

Mies van der Rohe, in many of his representations, brought together different visual devices, as in the case of the illustrations he produced for the Row House with the Court and the Museum for a Small City project (1942), where he combined the technique of the photo-collage or photo-montage with the linear or nonlinear perspective. In some cases, Mies did not use at all linear perspective. He implied it and used only the cut-outs of reproductions of images and artworks, as in some of his representations for the Small City Museum, in which the frontality of the way the reproductions of Pablo Picasso's painting Guernica (1937) framed by Aristide Maillol's sculptures Monument to Paul Cézanne (1912-1925) and Night (1909), and of the images of the nature scenes outside the window are placed imply the existence of a viewer. These representations invite the viewers to imagine that they move through the represented space. In the case of the combined elevation and section for the Theatre project of 1947, he used only frontal surfaces: one gridded surface designed with graphite ink and colored yellow and the other created using cut-and-pasted papers, and cut-and-pasted photo-reproductions. In a collage for the Concert Hall (1942), he did not use any traces of lines. Despite the fact that the way he fabricated was based on the use of the the technique of collage, it gives a sense of depth and linear perspective.

The use of the images of cut-outs of reproductions of real artworks for his collages or montages reinforces the cultural reading of his space assemblages. The placement of these cut-outs of reproductions of real artworks on the grid of the linear perspective views produces matrixes on which the ambiguities of cultural objects are unfolded. These choices of Mies van der Rohe make us think that he was interested in the multiple layers of the interpretation of images. This becomes evident in a collage he produced for the Concert Hall. In this case, Mies van der Rohe converted the image of the military warehouse into a cultural sign. In order to do so, he used the image of a statue of an ancient Buddha, at a first place, and then he added the title “Concert Hall", at a second place. Mies van der Rohe through the use of the reproduction of the image of a military warehouse, the placement of a statue and the written message aimed to convey an argument. The importance of Mies van der Rohe's aforementioned gesture lies on the fact that through the use of these three devices he turns abstract objects into cultural objects. Another instance in which Mies van der Rohe did not use at all conventional perspective, but he utilized only collage or photomontage was his collage for the Convention Hall. In this case, he used a picture of attendees at the 1952 U.S. Republican National Convention from Life magazine. What is of great interest in this case is the fact that Mies van der Rohe brought together many copies of the same image in order to create multiple vanishing points.

The techniques of the collage and montage are considered as avant-garde techniques. However, the technique of perspective is considered as non-avantgarde. Mies van der Rohe combined the two techniques in a way that challenged the very conventions of perspective and its philosophical implications. Collage and montage as techniques are opposed to perspective and are symbolic forms of modernity. Mies van der Rohe brought together these two opposed means of representation. The outcome of this strategy invokes a mode of viewing architectural representations that manages to activate modes of perception that are not reducible to the ways that are provoked by each of the aforementioned visual representation tool. In this sense, we could claim that in Mies van der Rohe'hs representations the disjunction of avant-garde and non-avantgarde techniques activates a mode of perception that is special to Mies. Martino Stierli notes in "Mies Montage" regarding this issue: 'montage and collage have different qualities of visuality and tactility. The inclusion of ‘reality fragments' (Peter Bürger) means that collage is subject to tactile perception; montage, conversely, is not.”[13]. Peter Bürger writes, in Theory of the Avant-Garde, regarding Cubist collage:

the reality fragments remain largely subordinate to the aesthetic composition, which seeks to create a balance of individual elements (volume, colours, etc). The intent can best be defined as tentative: although there is a destruction of the organic work that portrays reality, art itself is not being called into question”[14].

Following Peter Birger and Martino Stierli, we could argue that at the core of collage is the incorporation of reality fragments, which in contrast to montage, provokes a tactile perception. The technique of montage emerged in the circle of the Dadaists after the First World War. It was at the center of the avant-garde discourse. A distinction that would be useful for problematizing Mies’s conception of montage is the distinction that Jacques Ranciére draws between “dialectical montage” and “symbolic montage”. According to Rancière, “dialectical montage” reveals a reality of desires and dreams, hidden behind the apparent reality, while “symbolic montage” creates analogies by drawing together unrelated elements, proceeding by allusion. In many instances, Mies used real pieces of materials, such as pieces of flag, wood, veneer, or glass, and not only small reproductions of artworks. The tendency of Mies to bring together unrelated elements makes us think that he could be classified in the second category mentioned by Jacques Ranciére, that is to say “symbolic montage”.

Notes

1 Nicholas Temple, Disclosing Horizons: Architecture, Perspective and Redemptive Space (Oxon and New York: Routledge, 2007), 237.

2 Mark Pimlott, Without and Within: Essays on Territory and the Interior (Rotterdam: Episode publishers, 2007), 42.

3 Robin Evans, “Mies van der Rohe’s Paradoxical Symmetries”, AA Files, 19 (1990): 56-68; Evans, Translations from Drawing to Building and Other Essays (London: Architectural Association, 1997), 233-277.

4 Ibid., 253.

5 Fritz Neumeyer, “A World in Itself: Architecture and Technology”, in Detlef Mertins, ed., The Presence of Mies (New York: Princeton Architectural Press, 1994), 54.

6 August Schmarsow, “The Essence of Architectural Creation”, in Robert Vischer, Harry Francis Mallgrave, Eleftherios Ikonomou, eds., Empathy, Form, and Space: Problems in German Aesthetics, 1873-1893 (Santa Monica, CA: Getty Center for the History of Art and the Humanities, 1994), 281-297; Schmarsow, Das Wesen der architektonischen Schoepfung (Leipzig: Karl W. Hiersemann, 1894).

7 Ibid.

8 IMitchell W. Schwarzer, “The Emergence of Architectural Space: August Schmarsow's Theory of 'Raumgestaltung", Assemblage, 15 (1991), 50.

9 Colin Rowe, Robert Slutzky, "Transparency: Literal and Phenomenal”, Perspecta, 8 (1963): 45-54.

10 Robert Vischer, Harry Francis Mallgrave, Eleftherios Ikonomou, eds. , Empathy, Form, and Space: Problems in German Aesthetics, 1873-1893 (Santa Monica: Getty Center for the History of Art and the Humanities, 1994), 40.

11 Schmarsow, “The Essence of Architectural Creation," in Vischer, Francis Mallgrave, Ikonomou, eds., Empathy, Form, and Space: Problems in German Aesthetics, 1873-1893, 281-297; Schmarsow, Das Wesen der architektonischen Schoepfung (Leipzig: Karl W. Hiersemann, 1894);

12 Alois Riegl, Die Spátrómische Kunstindustrie nach den Funden in ÓsterreichUngarn (Vienna: Osterreichische Staatsdruckerei, 1901); Riegl, “The Main Characteristics of the Late Roman Kunstwoller", in Christopher S. Wood, ed., The Vienna School Reader. Politics and Art Historical Method in the 1930s (New York: Zone Books, 2000), 87-104.

13 Martino Stierli, “Mies Montage", AA Files, 61 (20).

14 Peter Bürger cited in Steve Plumb, Neue Sachlichheit 1918-33: Unity and Diversity of an Art Movement (Amsterdam; New York: Rodopi, 2006), 59; Bürger, Theory of the Avant-Garde, trans. Michael Scaw (Manchester; Minneapolis: Manchester University Press/University of Minnesota Press, 1984).