A Talk with Mles van der Rohe: Christian Norberg-Schulz

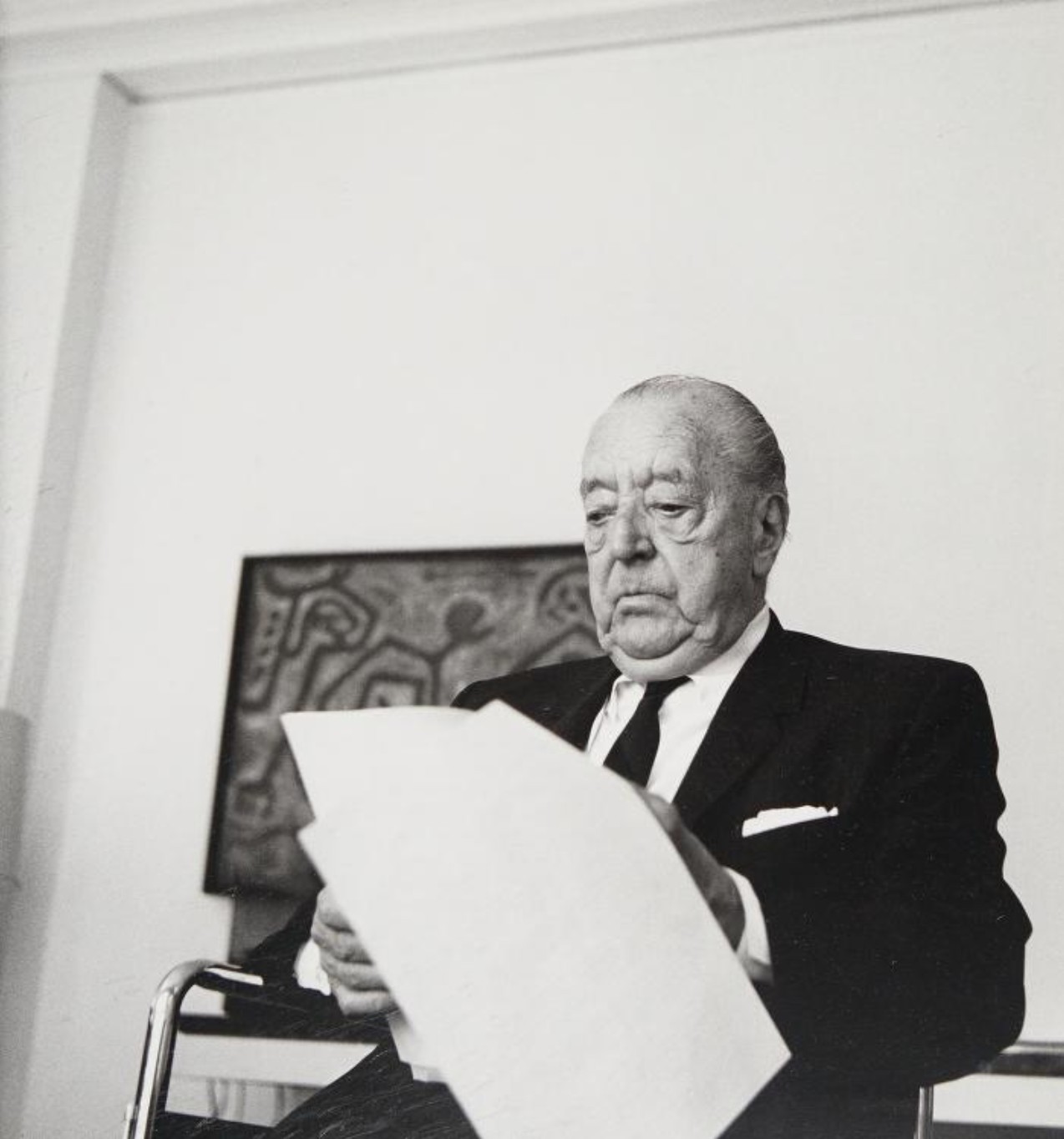

Mies van der Rohe in his apartment on Pearson Street in Chicago in 1964.

Mies van der Rohe is known as a man of few words. Unlike Le Corbusier, Wright, and Gropius, he has never defended his ideas in speech or text; his name only became familiar after the war. But the man behind the name remains as unknown as ever. As a replacement, so to speak, one has attempted to weave legends around him. The opponents of his architecture have discovered that he must be cold and without feelings, a formalist and logician who treats buildings like severe geometry. His adherents perceive him as a distant godhead floating above everything, divulging to his subalterns fundamental truths in the form of short aphorisms in professional journals. These aphorisms contain a certain mystical poetry reminiscent of the medieval mystic Meister Eckhart.

His office in Chicago is full of models of all sizes, very beautiful models of entire buildings, but also of individual corners and details. It is the same in the design rooms of his department at the Institute of Technology. The students work like professional metalworkers and construct detailed skeletons of large proportions. Everything points more to “building” than to the drawing of "paper architecture.” The main thing is the model, and the drawings are nothing but tools for the building site. The Institute of Technology constantly gets bigger. Mies is the planner. That way the students have a regular building practice during their courses of study.

"As you see, we are primarily interested in clear construction” ‘said Mies. "But is it not the variable ground plan that is typical for your school?” I asked somewhat surprised, for most of those writing on Mies emphasize the so-called variable ground plan.

“The variable ground plan and a clear construction cannot be viewed separately. Clear construction is the basis for a free ground plan. if no clear-cut structure results we lose all interest. We begin by asking ourselves what it is that we have to build: an open hall or a conventional construction type—then we work ourselves through this chosen type down to the smallest detail before we begin to solve the problem of the ground plan. If you solve the ground plan or the room sequence first, everything gets blocked and a clear construction becomes impossible.”

"What do you understand by ‘clear construction’?" “Could one say that such a methodical construction should also serve to hold the building formally together?"

"Yes, the structure is the backbone of the whole and makes the variable ground plan possible. Without this backbone, the ground plan would not be free, but chaotically blocked.”

Mies then began to explain two of his most important projects, Crown Hall and the Mannheim Theater. Both are large halls formed of roofs and walls suspended from a gigantic steel structure. Crown Hall has two floor levels, one of which is half underground. It houses the workshop of the Institute of Design, while Mies's own Department of Architecture is housed in the upper hall. Malicious tongues have it that Mies has arranged this because he does not esteem the pedagogical methods of the Institute of Design and wishes–quite literally—to keep it down.

“We do not like the word ‘design.’ It means everything and nothing. Many believe they can do it all fashion a comb and build a railroad station. The result, nothing is done well. We are only concerned with building. We prefer ‘building’ to ‘architecture'; and the best results belong in the realm of the ‘building art. Many schools get lost in sociology and design; the result is that they forget to build. The building art begins with the careful fitting of two bricks. Our teaching aims at training the eye and the hand. In the first year we teach our students to draw exactly and carefully, in the second year technology, and in the third the elements of planning, such as kitchens, bathrooms, bedrooms, closets, etc.”

Crown Hall and the Mannheim Theater are symmetrical; I asked Mies why so many of his buildings are symmetrical and whether symmetry is important.

“Why should buildings not be symmetrical? With most buildings on this campus it is quite natural that the steps are on both sides, the auditorium or the entrance hall in the middle. That is how buildings become symmetrical, namely when it is natural. But aside from that we put not the slightest value on symmetry.”

Another remarkable similarity between the two buildings is the exterior construction. “Why do you always repeat the same construction principle instead of experimenting with new possibilities?"

“If we wanted to invent something new every day we would get nowhere. It costs nothing to invent interesting forms, yet it requires much additional effort to work something through. I frequently employ an example of Viollet-le-Duc in my teaching. He has shown that the three hundred years it took to develop the Gothic cathedral were above all due to a working through and improving of the same construction type. We limit ourselves to the construction that is possible at the moment and attempt to clarify it in all details. In this way we want to lay a basis for future development.”

Apparently Mies is very fond of the Mannheim Theater: he describes it in all details. He emphasizes that the complicated ground’ plans conformed to the demands of the competition program. It called for two stages that—having identical technical installations—can be played on independently of each other.

While Mies worked on some projects for months and years, this building was designed within a few weeks of hectic work, in the winter of 1952-53. Students who helped him recounted how he would sit for hours in front of the large model in his dark suit "as if for a wedding,” the inevitable cigar in his hand.

“As you see, the entire building is a single large room. We believe that this is the most economical and most practical way, of building today. The purposes for which a building is used are constantly changing and we cannot afford to tear down the building each time. That is why we have revised Sullivan's formula ‘form follows function’ and construct a practical and economical space into which we fit the functions. In the Mannheim building, stage and auditorium are independent of the steel construction. The large auditorium juts out from its concrete base much like a hand from the wrist.”

There were still many things to ask; Mies suggested continuing the conversation in his apartment over a glass. He lives in an old-fashioned apartment. The large living room has two white walls, the furniture is simple, cubist and black. On the walls glow large pictures by Paul Klee. The maid serves on a low Chinese table, as if she wanted to arrange a Miesian ground plan.

"One is surprised that you collect Klee pictures; one thinks that does not fit your building.”

“I hope to make my buildings neutral frames in which man and artworks can carry on their own lives. To do that one needs a respectful attitude toward things."

“If you view your buildings as neutral frames, what role does nature play with respect to the buildings?"

“Nature, too, shall live its own life. We must beware not to disrupt it with the color of our houses and interior fittings. Yet we should attempt to bring nature, houses, and human beings together into a higher unity. If you view nature through the glass walls of the Farnsworth House, it gains a more profound significance than if viewed from outside. This way more is said about nature—it becomes a part of a larger whole.”

“I have noticed that you rarely make a normal corner in your buildings but that you let one wall be the corner and separate it from the other wall.”

“The reason for that is that a normal corner formation appears massive, something that is difficult to combine with a variable ground plan. The free ground plan is a new concept and has its own ‘grammar'—just like a language. Many believe that the variable ground plan implies total freedom. That is a misunderstanding. It demands just as much discipline and intelligence from the architect as the conventional ground plan, it demands, for example, that enclosed elements, and they are always needed, be separated from the outside walls—as in the Farnsworth House. Only that way can a free space be obtained."

“Many criticize you for adhering to the right angle. In a project of the thirties, though, you employed, together with a free ground plan, curved walls."

"I have nothing against acute angles or curves provided they are done well. Up to now I have never seen anybody who has truly mastered them. The architects of the baroque mastered these things—but they represented the last stage of a long development.”

Our conversation ended late at night. Mies van der Rohe is not the man of the legends. He is a warm-hearted and friendly man, who demands only one thing from his co-workers: the same humble attitude toward things that he himself has.

Baukunst und Werkform 11 no. 11 (1958)