Mies and Photomontage, 1910—38: Andres Lepik

1. Mies van der Rohe. Bismarck Monument Project, Bingen. 1910

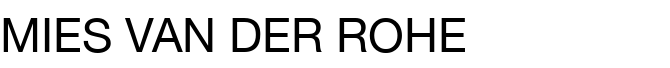

2. Mies van der Rohe. Friedrichstrasse Skyscraper Project. 1921. Perspective from north, first version: photograph of lost photomontage.

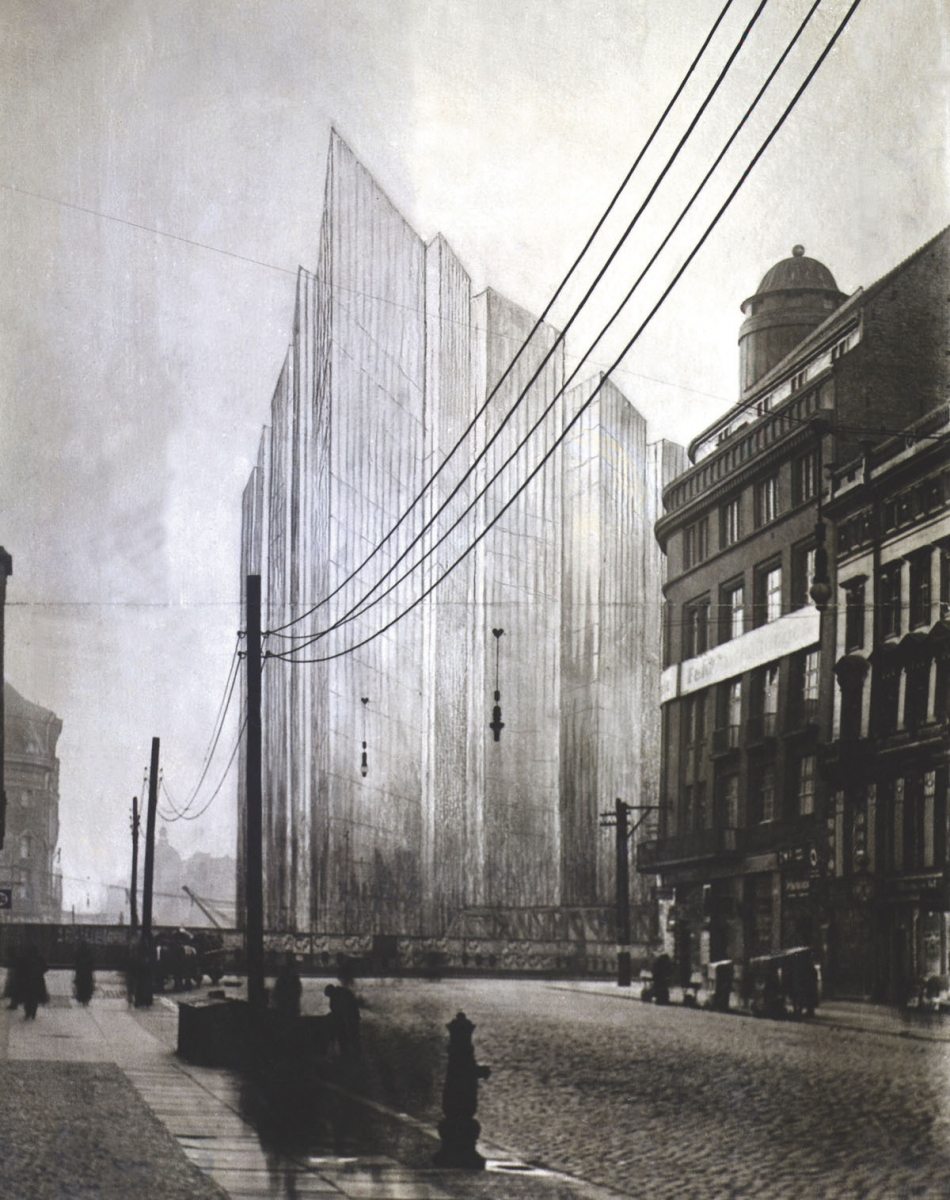

3. Mies van der Rohe. Glass Skyscraper Project. 1922.View of model: airbrushed gouache on gelatin silver photograph.

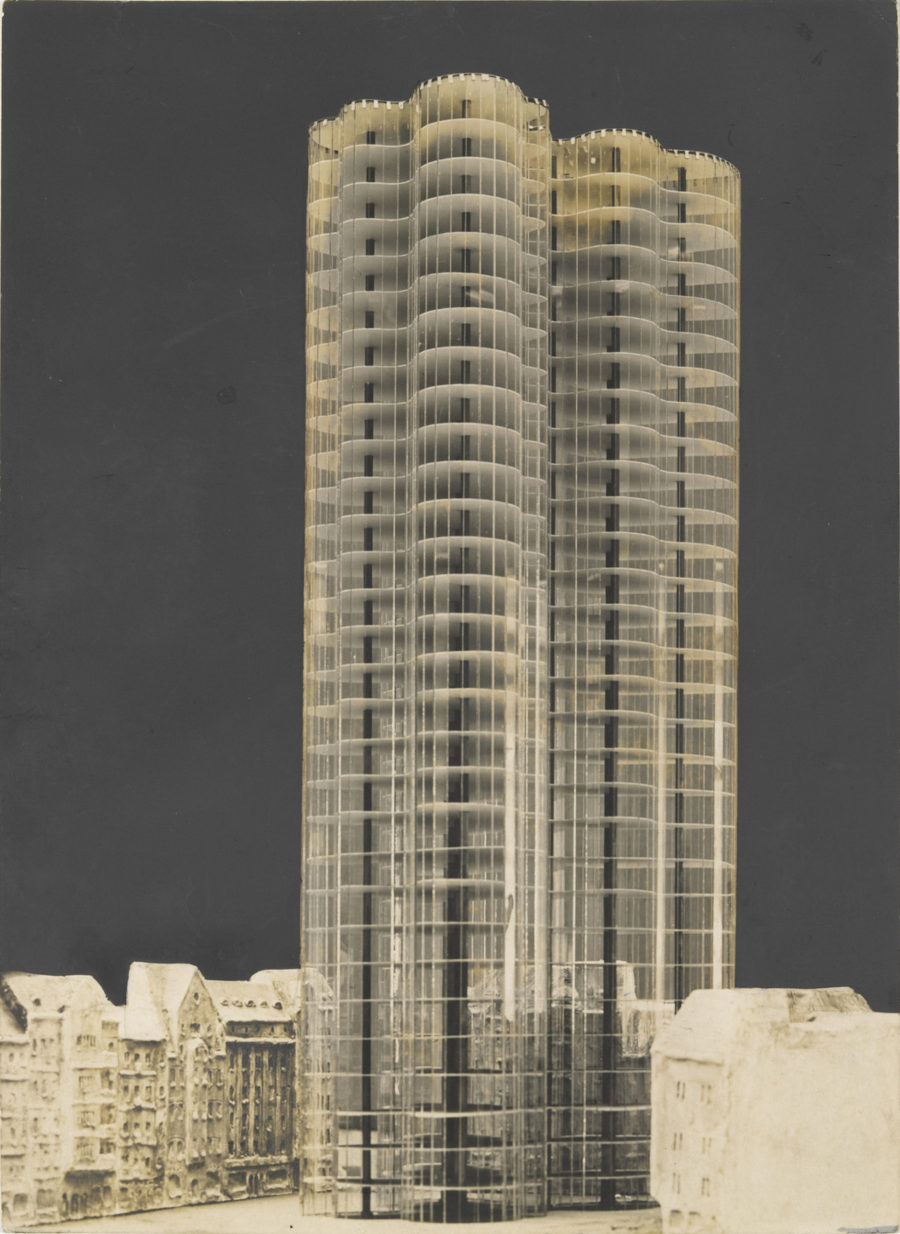

4. Mies van der Rohe. S. Adam Department Store Project, Berlin. 1928-29. Photomontage: airbrushed gouache on gelatin silver photograph.

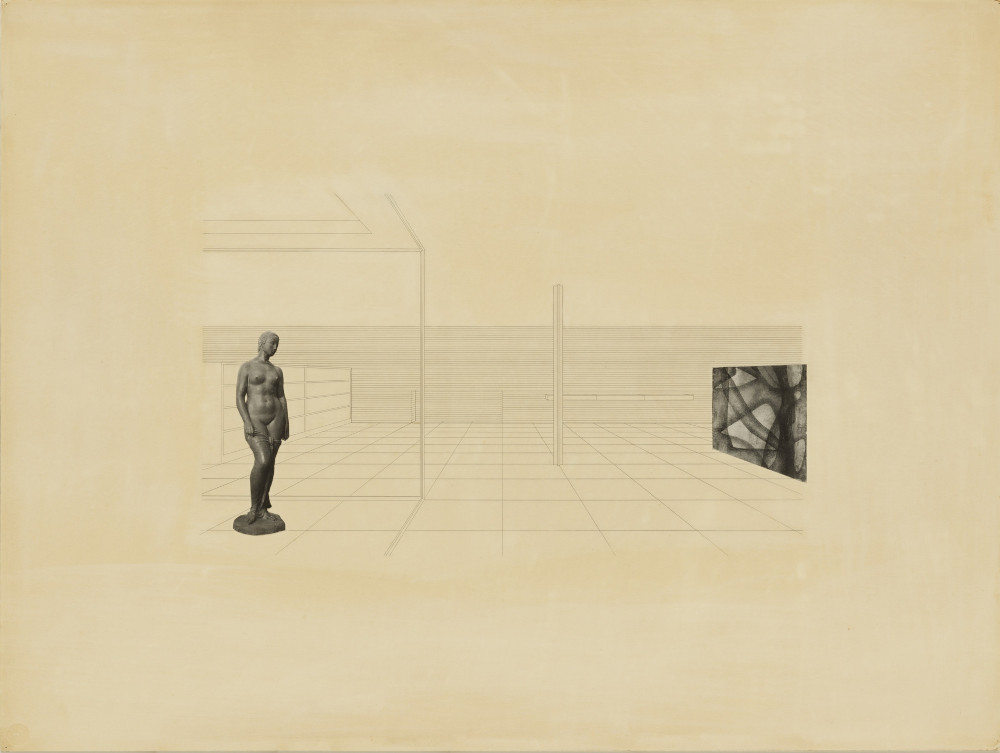

5. Mies van der Rohe. Court-House Project. After 1938. Interior perspective: pencil and cut-out reproductions (of Wilhelm Lehmbruck's Standing Figure and an unidentified painting) on illustration board.

Mies’s prominence in our perception of the architecture of modernism is largely due to his ability to capture programmatic ideas in pictorial form. Like Le Corbusier, by the beginning of the 1920s Mies knew how to create a public image of himself as a leading modern architect. To do so he devised impressive presentations of his work, both in exhibitions and in print, and carefully supervised the creation and reproduction of pictures and texts on his projects. He early on assumed responsibility for the image the public would form of him.

Mies's surviving drawings record virtually nothing of his first designs, from the period 1905-10. There are no drawings clearly identified as his relating to the Riehl House (1906-7) or any other project of the period, whether he worked on it independently or as an employee in the offices of Bruno Paul or Peter Behrens. Yet his training in an Aachen trade school had certainly given him experience as a draftsman well before he even considered a career as an architect.[1] It was his confidence in his drawing skills that led to his first paying job, which itself gave him practice in drawing: every workday for two years, he stood at a drafting board preparing working drawings for stucco architectural ornaments.[2]

Over 3,000 drawings from 1910-38 are preserved in The Museum of Modern Art's Mies van der Rohe Archive.[3] Of these, the vast majority date from after 1921. Whether at the Museum or elsewhere, only a few finished renderings survive from earlier years, and these generally exhibit nothing of Mies's characteristic signature. (He weeded out a lot of his papers in the 1920s.[4]) In view of these numbers, it is striking that for Mies's first competition entry, for the Bismarck Monument proposed for Bingen in 1910, there survive not only two large-format, color presentation drawings of exterior and courtyard views but also his first photomontage.[5]

In incorporating his drawings in photomontages, Mies took up a form of architectural presentation initially used mainly in competition situations. Around 1900, Friedrich von Thiersch and other architects preparing competition submissions began the practice of mounting a drawing on a photograph of a building's possible setting, making for greater realism and a more convincing simulation than the standard perspective drawings these images supplemented.[6]

Subsequently, as the use of photography to present architecture both in professional journals and for more general audiences became increasingly widespread, the addition of drawings to photographs became more common. Wherever Mies first encountered the technique,[7] he adopted it as ideally suited for the presentation of architectural concepts in the growing number of publications available to him.

The Bismarck Monument

For the proposed Bismarck Monument, we have, in addition to Mies's large presentation drawings and a photomontage (fig. 1), a preliminary drawing that seems to have been made as a guide for the person who made the montage. In the upper section of this horizontal sheet is a view of the monument, its base beginning halfway up the high hill that at this point defines the riverbank. The drawing is summary in its details, but the form of the structure seems to have been finalized, ft is shown at an angle from below, as if the viewer were approaching it on foot. Below the image of the monument is a diagonal dotted line indicating where drawing and photograph were to join. In the lower third of the sheet, the footpath is roughly sketched in, just as it would appear in the photograph. On the left is another section set off by a dotted line, marking an area where the photograph was to be extended with an additional drawing: the photograph chosen for the montage,[8] of a path between vineyards, was apparently too small to cover the full width of the proposed image, so additional vines needed to be sketched in to stretch it.

Mies's inclusion on the drawing of the numerals 1, 2, and 3, as well as of the dimensions he envisioned —"mat size 1.00 x 0.50 size of actual picture 0.91 x 0.72"—suggests that the montage was to be executed by someone else. His detailed directions show how carefully he wanted his draftsmanship to be juxtaposed with the photograph.[9] His talent for presenting his ideas is obvious if one compares his submission with that of Gropius, for example, which adopts a quite similar point of view and is formally quite close to his, but fails to attain the same realism, appearing more two-dimensional.[10] Mies deliberately used photomontage in addition to or perhaps even instead of his own large-format colored drawings (whether these drawings were actually submitted to the competition is unclear) to simulate the effect of the structure in an actual setting. He manipulated photographic "reality" to create an impression.

After the Bismarck Monument, it was a while before Mies created another photomontage. In his commissions for private homes like the Perls House (1911-12), the Werner House (1912-13), and the Urbig House (1915-17), traditional views, cross-sections, and floor plans were adequate for the communication between architect and client. Photomontage was more public in function, and it only reappears in Mies's drawings to illustrate the visionary building ideas that he began to develop in the early 1920s. The actual construction of these buildings was improbable at the time, but the publication and distribution of the designs for them were important to him. These designs would only become well-known through such theatrical presentation.

Mies's interest in publishing may have been inspired by the architectural books and journals of his day, particularly the important series of portfolios of works by contemporary architects begun by Wasmuth, Berlin, in 1900. The Wasmuth collection Ausgejuhrte Bauten und Entwurfe von Frank Lloyd Wright (Executed buildings and designs by Frank Lloyd Wright), along with a Berlin exhibition of its illustrations, was largely responsible for making Wright influential in Germany.[11] Beginning in 1922, with his shrewd publications of designs and accompanying statements in the journals Friihlicht and G, Mies became actively engaged in the theoretical discussions of his time. Allergic to writing as he was, his statements tended to be concise,[12] so that the reproductions that accompanied them took on added importance, not just as illustrations to the texts but as independent statements.

The Friedrichstrasse Skyscraper

Mies's photomontages of the skyscraper he envisioned for a site next to Berlin's Friedrichstrasse train station are among the crucial incunabula of architectural presentation in the twentieth century. To the best of our knowledge, they were not included in the material Mies submitted to the 1921 competition for the site; made in unusually large formats —and therefore surely unacceptable as competition submissions — they only make sense as later creations for the purposes of exhibition and publication.[13] These montages, frequently reproduced both in their final form and in earlier stages, reveal an evolution from a basically photorealist style to one of Expressionist exaggeration.

The basis for the series was a single enlarged photograph of Friedrichstrasse, a dramatic perspective looking south along the street. Into this image Mies inserted a drawing of his sharp-edged glass skyscraper, a transparent, almost ethereal vision.[14] The contrast between the late-nineteenth-century facades on both sides of the street, recognizable as real by the shop signs if nothing else, and the delicately rendered glass structure could not be greater, and in the earliest known version of the montage (fig. 2) it breaks the photographed reality and the visionary drawing virtually into different picture planes. In capital letters along the bottom edge is a caption, which is incomplete —"blik von der oberen friedrichstr . . ." (View of Upper Friedrichstr . . .) —suggesting that this early montage, now lost, was an abandoned first stage. When it was published in G, in June 1924, the lower edge was cropped,[15 as it was in subsequent publications.[16] The fold across the middle, visible even in the reproduction, suggests that this montage, like the later ones, was routinely folded for transport to exhibitions.

In a subsequent version, still working with the same enlargement, Mies managed to bring the planes of photograph and drawing closer together, melding them into a unified whole. He did so by darkening the forms in the photograph with thick crayon, which made them more abstract, while at the same time adding details to the skyscraper, including an indication of individual floors. In this version the darkening of the photograph does not fully cover it; a lighter border is left at the bottom and along the right side. Apparently Mies was already considering cropping the image —as he did in the final stage, at all four edges, so that the skyscraper dominates the picture. Comparing this version (first reproduced in Frühlicht in 1922[17] and now in the collection of The Museum of Modern Art) with reproductions of it in early publications, one notes that at some point its focus was further narrowed by a second cropping of the edges. There is another, important difference between this final image and the earlier stages: this image is entirely a drawing. Not only has the photograph's record of reality been reduced to a schematic frame, it has been transferred into an image drawn in charcoal. From the earlier versions of the montage, in which the dominant impression is the simulation of an actual street scene, Mies ultimately arrived at an autonomous image.[18]

In reworking his montage in this way, Mies was developing a presentation medium for his designs that was all his own. His goal, clearly, was not a photorealist simulation of the project but the strongest possible image. In fact everything suggests that this entire series of large montages and drawings was produced for either publication or exhibition, each one moving farther from the original context of the architectural competition. This helps to explain why questions of technical feasibility appear to have concerned Mies barely at all in these buildings.[19] During this period, he was employing the same presentation technique of framing an architectural vision with darkened older structures for his Concrete Office Building Project (1923), also published in G and shown at exhibition, and produced independently of any competition.

Around 1922, Mies had a model made of his Glass Skyscraper Project, perhaps a second design for the Friedrichstrasse site. He photographed this model in settings both simulated and real, then published the photographs (fig. 3);.[20] These images, with their caricaturish depiction of older structures supposedly surrounding the skyscraper, immediately remind one of Expressionist architecture in the German film of the period, for example Hans Poelzig's crooked clay huts in The Golem (1920). Here Mies made no attempt to reproduce Friedrichstrasse as it actually was; the illustration was programmatic. The photographs took the process of simulation one step farther. Meanwhile, in a charcoal drawing from the same year, Mies reverted to a more familiar medium, which, however, he used to create an expressive, visionary presentation in the form of a monumental rendering.

Although these diverse representations show Mies exploring an Expressionist exaggeration of the view from the pedestrian perspective, in the charcoal drawings embedded in them he completely abandons the notion of simulating realistic views. These images present his designs as virtually abstract structures, looming up out of architectural surroundings that are either merely suggested or omitted altogether. Mies rarely signed his drawings, but he signed the second of these ones, suggesting that he ascribed particular value to it. This was the drawing he used as the cover of the third issue of G, in June 1924 21—the issue he financed himself, at the request of the journal's editor, Hans Richter.

Dada

Montage and collage were favored mediums of expression for Berlin Dadaists such as Hannah Hoch, Raoul Hausmann, and John Heartfield, all of whom used the two techniques from 1919 or so onward. Mies's attendance at the opening of Berlin's First International Dada Fair—on June 30, 1920, in the salon of Dr. Otto Burchard (p. 106, frontispiece)—suggests his personal relationship with the Dada community in Berlin; with Hoch especially he was on friendly terms for many years, beginning around 1919.[22] But despite these connections, his montages bear little relation to Dadaist thinking.[23] Those artists used montage and collage mainly to dissect existing pictorial realities and then to rearrange them into new, ambiguous unities. For them, drawing was an unimportant conventional skill.[24] Mies's montages, on the other hand, derived their strength from drawing, and preserve an inner axial and spatial unity.

In a larger sense, however, there is a quality of Mies's montages that links them to Dada: their self-promotional aspect. The Dadaists were famous for their exploitation of newspapers and journals, for example Neue Jugend (beginning in 1917), Die Pleite (beginning in 1919), and Der Gegner (beginning in 1920), all published by Malik Verlag. In the immediate postwar period, when actual building commissions were hard to come by, many architects resorted to print to express their ideas. Bruno Taut's Stadtkrone (City crown) and Alpine Architektur books both appeared in 1919. In 1920, Le Corbusier began publishing his journal L'Esprit nouveau, Taut's journal Frühlicht, which represents the culmination of visionary Expressionist architectural theory, began publication in 1921. It was in Frühlicht, in 1922, that Mies published his first skyscraper design for the Friedrichstrasse site, allowing himself to be associated with the exalted, almost mythic vision of glass architecture that had been developing since 1914.[25] This was by no means the context in which he wished to be understood; yet none of the many Dadaist publications, all propagandistically antibourgeois, provided the right platform for his ideas either. Mies had no desire to shock his clients, to whom he had owed profitable commissions even during the war. So it was that in 1923 he declared his commitment to Richter's G, a far less political forum in which he published some of his core ideas and designs of the period. With its experimental typographic design, the journal, to which Mies also provided financial support, resembled the short lived publications of the Dadaists, and occasionally made room for their contributions. It was also inspired in part by the Dutch journal De Stijl and by the Russian Constructivists.

Mies often used montage in his presentations even after 1922, for example in his Urban Design Proposal for Alexanderplatz (1929) and in his S. Adam Department Store Project in Berlin (1928-29; fig. 4). He also submitted a montage to the competition for a Bank and Office Building in Stuttgart (1928), as also did Paul Bonatz, Alfred Fischer, and various other architects; in fact, since all of these submissions were based on the same photograph, it seems likely that such a presentation was required.[26] In presenting his designs for the Friedrichstrasse Office Building Project in 1929, Mies again superimposed drawings on photographs of the existing urban fabric. Dramatic as these images are, they all use the same technique that Mies had worked out in 1910, in his montages of the Bismarck Monument.

From Inside Out

Until 1928—29, Mies used montage exclusively in exterior views of his major projects. After 1930, however, he developed another type of montage to show interiors, giving otherwise straightforward perspective drawings, albeit of fluid spatial arrangements structured by walls, columns, and glass, a wholly different aura by inserting into them photographs of real works of art. This practice is most evident after 1938, but foreshadowings of it can he seen in Mies's drawings—in an interior view for the German Pavilion, Barcelona, of 1928-29, and in another for the Tugendhat House of 1928-30, for example, in both of which Mies draws a sculpture by Wilhelm Lehmbruck. From the time of his design for the Krefeld Golf Club Project (1930) onward,[27] Mies's drawings increasingly represent architecture from the inside out, and in a drawing for the Golf Club, a delicate perspective of a pavilion like interior and an outdoor courtyard barely separated from each other by a glass wall, we again see a recumbent sculpture in the manner of Lehmbruck (fig. 10), much as the Georg Kolbe figure Dawn had appeared in a courtyard at the German Pavilion. The sculpture serves as a point of reference or orientation in the representation of interior versus exterior. The perspective indicated by a square grid marked in the floor creates an effect of large space, and the vanishing point for these lines is not in the center of the drawing but decidedly to one side.[28]

In a number of his court-house designs of the 1930s, Mies returned to montage as a way of creating "pictures" to represent his ideas in exhibitions. Some of these presentations include real wood veneer, and reproductions of sculptures (for example fig. 5, which shows a standing figure by Lehmbruck from 1919) or paintings. All of these montages were created after 1938, some of them perhaps a decade or so later, in preparation for the exhibition of Mies's work at The Museum of Modern Art in 1947.[29] From the late 1930s on, Mies included reproductions of art in his drawings so regularly that it must have been a favorite presentation technique. One thinks of the familiar montages for the Resor House Project (1937-38), the Museum for a Small City Project (1942), the Concert Hall Project (1942),and the Convention Hall Project (1953-54).[30] In fact Mies used the technique as late as his last major commission, the New National Gallery in Berlin (1962-68).

Montage, clearly, was one of Mies's favorite methods of presentation,[31] and his pictures were so effective that some of his pupils adopted the technique as well.[32] A generation later, in their effort to deconstruct his legacy, postmodern critics of modernism have used montage them selves[33]—or, as in the case of the polemical architectural group Archigram, have brazenly reinterpreted his montages for their own ends.[34] The architect Renzo Piano, in a corner view showing his recent design for a high-rise on Potsdamer Platz in Berlin, clearly alludes to Mies's first montages of the Friedrichstrasse Skyscraper of 1921.[35]

While Mies's writings tend to be laconic and abstract, his montages are highly expressive, a quality owed largely to their elegant draftsmanship. Anything but products of "chance,”[36] they are a logical complement to his theoretical statements and his more traditional drawings. Although Mies destroyed any number of drawings from his early years, he shrewdly preserved his montages, selecting them carefully for the various publications he oversaw, or into which he had input—even including the book accompanying his exhibition at The Museum of Modern Art in 1947. Even our view of the structures he actually built is influenced by these images, to the extent that we occasionally find a straightforward photograph of one so dramatic that we suspect it of being a montage.

Notes

1 See Franz Schulze, A Critical Biography, pp. 14, 15.

2 He himself said that it was the drawings he submitted in response to a classified ad that allowed him to move to Berlin. See ibid., p. 18.

3 Arthur Drexler, ed., The Mies van der Rohe Archive,1:xv.

4 See Fritz Neumeyer, The Artless Word, p. 170.

5 I use the term "montage" for all of Mies's presentations combining drawing and photography, although it would often be more correct to speak of drawings inserted into photographs. Unlike collage, which aims to rupture pictorial unity, montage preserves a unified pictorial form.

6 See Winfried Nerdinger, Die Architekturzeichnung: Horn barocken Idealplan zur Axonometrie (Munich: Prestel, 1986), pp. 142-43 and note 6.

7 Mies may have come across the montage technique early on, in his father's workshop; see Rolf Sachsse, Bild und Bau: Zur Nutzung technischer Medien beim Entwerfen von Architektur (Braunschweig and Wiesbaden: Vieweg, 1997), p. 148.

8 In this case the photograph was not necessarily taken at the spot in question.

9 Another photomontage of the Bismarck Monument with a more distant view has been lost, but is documented by a photograph; see Drexler, ed.. The Mies van der Rohe Archive, 1:3.

10 See Walter Gropius, exh. cat. (Berlin: Bauhaus-Archiv, 1985), p. 216, W6.

11 Mies could also have seen an effective combination of realized and unrealized designs in Karl Friedrich Schinkel's Sammlung architektonis-cher Entwiirfe. See Sachsse, Bild und Bau, p. 26. The same combination appears in Schinkel's Orianda publication, which Mies owned.

12 See Neumeyer, The Artless Word, p. 21.

13 See Florian Zimmermann, ed., Der Schrei nach dem Turmhaus: Der Ideenwettbewerb Hoehham am BahnhofFriedrichstrasse Berlin 1921-22 (Berlin: Bauhaus-Archiv, 1988), p. 106, and Christian Wolsdorff, entry for cat. no. 268 in Magdalena Droste and Jeanine Fiedler, eds., Experiment Bauhaus: Das Bauhaus-Archiv (West) zu Cast im Bauhaus Dessau, exh. cat. (Berlin: Kupfergraben, 1988), p. 316.

14 Drexler, ed., The Mies van der Rohe Archive, 1:xx.

15 G: Material zur elementaren Gestaltung no. 3 (June 1924): n.p. [13].

16 See, for example, Paul Westheim, "Mies van der Rohe: Entwicklung eines Architekten," Das Kunstblatt 11, no. 2 (February 1927): 58 right.

17 Frühlicht 1, no. 4 (1922): 124.

18 Another montage, now lost, showing the Friedrichstrasse Skyscraper from the south (p. 43, fig. 13), explores an extreme contrast between drawing and photograph—apparently an experiment that was abandoned. A charcoal drawing was probably a study for it; see Drexler, ed., The Mies van der Rohe Archive, 1:no. 20.5. See the juxtaposition in Zimmermann, Der Schrei nach dem Turmhaus, p. 108.

19 '"One so rarely requires of men the impossible' (Goethe)." Bruno Taut, Alpine Architektur (Hagen: Folkwang-Verlag, 1919), p. 10.

20 Frühlicht 1, no. 4 (1922): 122. See also Drexler, ed., The Mies van der Rohe Archive, 1:62: "The Archive has several photographs showing the glass model placed outside the window of Mies's office." In a photograph of the Internationale Architektur exhibition at the Bauhaus, Weimar, in 1923, the models of the Glass Skyscraper and of the Concrete Office Building stand next to each other (p. 120, fig. 16).

21 In G the signature is replaced by the initials “M.v.d.R.”

22 See Detlef Mertins, "Architectures of Becoming: Mies van der Rohe and the Avant-Garde," in the present volume, and particularly its frontispiece, p. 106. On Mies and Hannah Hoch see the many references to him, extending to 1964, in Hannah Hoch: Eine Lebenseollage, 6 vols. (Berlin: Stiftung Archiv der Akademie der Ktinste, 1989).

23 See Sachsse, Bild und Bau, p. 149.

24 "Whereas previously huge amounts of time, devotion, and effort had been expended on the painting of a body, a hat, a shadow, etc., we need only pick up a pair of scissors and cut out from paintings and photographs the things we can use." Wieland Herzfelde, in Karl Rifa, ed., Dada Berlin: Texte, Manifeste, Aktionen (Stuttgart: Reclam, 1977), p. 118.

25 See Hanno-Walter Krufi, Geschichte der Architekturtheorie (Munich: Beck, 1985), pp. 429-30.

26 Heinrich Klotz, ed., Mies van der Rohe: Vorbild und Vermachtnis (Frankfurt am Main: Deutsches Architekturmuseum, 1986), pp. 114-16, cat. nos. 17, 19, 21a, 22b, 25a.

27 Drexler, ed., The Mies van der Rohe Archive, 3: nos. 19.66, 19.67, and Schulze, ed., The Mies van der Rohe Archive: Supplementary Drawings, 6:5, no. 19.52.

28 Here Mies may have been thinking of Schinkel's Sammlung architektonischer Entwiirfe, which features similar ways of depicting interior spaces.

29 I am grateful to Terence Riley for suggesting this possibility.

30 See Neil Levine, '"The Significance of Facts': Mies's Collages Up Close and Personal," Assemblage 37 (1998): 70-110.

31 To say that "Mies's medium was montage," as Sachsse does, nevertheless goes too far; see Sachsse, Bild und Bau, p. 147.

32 See Klotz, ed., Vorbild und Vermachtnis, cat. nos. 108, 109, 122. Many of the montages associated with Mies's later projects may have been produced by his staff and students.

33 See the frequently reproduced montage of 1978 by Stanley Tigerman, in which Mies's Crown Hall in Chicago is seen sinking into the sea like the Titanic. Reproduced in Neumeyer, The Artless Word, p. xvi.

34 For example the montage Pool Enclosure for Rod Stewart, Ascot, from 1972. Also Hans Hollein and others.

35 In the exhibition of his work at the New National Gallery, Berlin (that is, in the building that was Mies's last major project), in the summer of 2000, Renzo Piano actually placed a reproduction of Mies's montage next to his view of his own building.

36 Notwithstanding Francesco Dal Co's argument that "It is no accident . . . that chance plays a dominant role in his collages." See Dal Co, "Einzigartigkeit: Mies van der Rohes philosophisch-kultureller Hintergrund," in Klotz, ed., Vorbild und Vermachtnis, p. 72.