Anselm Kiefer. Your Age and My Age and the Age of the World (Dein und mein Alter und das Alter der Welt), 1997.

Archaic Architectures 1997 / Cosmos and Star Paintings 1995-2001: Katharina Schmidt

The pyramid dominates the vast horizontal oblong format. A massive triangle, bare and rough, it thrusts upward to the full width of our view. Lofty and remote, the apex looms against an overcast sky. A minor displacement of the angle of view, a slight deviation from axial symmetry, endows this crude presence with a massive dynamism and conveys an impression of three dimensions, despite the simple geometric articulation of the picture surface. The sky is sandy, oppressive and remote; the horizon, largely concealed by the structure, is almost invisible. Akhet Khufru was the name given by the founder to this monument, and to the city and palace that accompanied it: Horizon of Cheops. The narrow, vertical notch in the masonry halfway up reveals that this is a view of the south side.

In the cycles of work in which he explores the contemporary resonances of complex themes from myth, history and art, Anselm Kiefer has often depicted architectural forms: massive interiors with interlocking wall patterns from which there is no escape. In reinterpreting derelict structures that have lost their original functions, he has succeeded to a startling degree in conveying the heedless treatment suffered by those structures, as well as their obstinate persistence. At the same time, he has stripped away many incrustations. Inscriptions indicate a change of use: tantalizing, surprising possibilities. A hopeless new start? A rational intervention? At once hermetic and charged with history, his exterior views show how the passage of time causes architecture and landscape to approximate to one another. Grab des unbekannten Malers (Tomb of the Unknown Painter) is the dedicatory inscription on one such monument, which grows out of a hillside like Max Ernst’s “Entire Cities”.1 Later on, Kiefer’s interest in ancient civilizations shifts somewhat from their myths to their building forms. Their ruins, the vestiges of their decay and all the signs of the departure of organic life offer occasions for new Vanitas images nourished by contemporary experience.

Cheops2 built himself a tomb, unprecedented both in its constructional technique and in its size, on a rocky outcrop in the Libyan Desert.3 The Great Pyramid attracted interest from an early date; its destruction also started early. The Greeks ranked it first among the Seven Wonders of the World; but, by the time the writers of antiquity described it, the glittering pyramidion at its apex and part of the apex itself were missing. The white limestone casing had also gone. Only in the Enlightenment did a growing spirit of scientific enquiry lead to the systematic investigation of the monument. To this day, researchers are still exploring its idiosyncrasies and enigmas. The narrow opening halfway up one side was caused by irresponsible excavation of the interior. In Kiefer’s painting, the crude break in the skin serves as a reference to the core of the architecture, and thus to its original function.

Kiefer’s majestic view, in which the stone surface appears as a rough, sculptural relief, and the clouds in broad, horizontal swathes, would surely have taken its place among the nostalgic products of Egyptomania and Orientalism, had we not eventually discovered its inscriptions. “dein und mein Alter und das Alter der Welt” (“your age and my age and the age of the world”), is written in the sky at top right; below, in blurred and weathered letters among the stone blocks of the base, is the dedication: “für Ingeborg Bachmann”.

From an early stage in his career, Kiefer began to integrate handwritten inscriptions—mostly cursive, and his own—into his compositions. This enabled him to hold a discreet balance between illusionistic spatial effect and the two-dimensional surface, and at the same time to displace a part of the painting’s effect from visual perception to reflection. This opens up additional layers of meaning. By using the obsolete formula of dedication as a visual device, Kiefer retrieves a distinctive level of significance. Ranging from subtle allusion to plain identification, his dedications are as varied in character as the dedicatees.4 Dedications are a weapon against oblivion; they contribute to the history of influences, and enable the artist to share his isolation with another person. Kiefer has recently spoken of the close affinity that he feels for the Austrian poet Ingeborg Bachmann, and he quotes her in several of his works.5 The line of hers that he includes in this painting,6 written in the clouds as if about to blow away across the desert, relates the individual human life to cosmic time.

In this poem, the authorial self speaks to a brother: a dialogue that translates, in painting, into the painter-viewer relationship—or is the artist addressing the pyramid?7 What is certain is that his links with Bachmann’s work extend beyond individual lines or poems. For, in the “Desert Chapter” of her novel Das Buch Franza, a woman in extreme distress of mind gives herself a mortal wound at the base of this same pyramid, “at this tomb”.8 The novel forms part of an ambitiously conceived “Varieties of Death Project”,9 which Bachmann intended as a tribute to the victims, the defenceless ones, those for whose sufferings no law exists. Kiefer inscribes Bachmann’s name on the greatest architectural work of humanity, and rededicates the empty tomb to her memory and in her spirit.

The Desert Paintings are more tranquil in composition, light and clayey in colour, and—except for those that are bound into books—vast in extent. Some of these works, too, are dedicated to Bachmann, a writer for whom the desert possessed existential significance both as a metaphor and—later—as a personal experience.10

Skimming across the arid wastes to the distant horizon, the eye is arrested by a line of poetry: “wach im Zigeunerlager und wach im Wustenzelt, es rinnt uns der Sand aus den Haaren”11 “Awake in the gypsy camp and awake in the desert tent, the sand trickles out of our hair”. The sentence is shared between the two halves of the painting: like a fence, it marks off the earth from the barely visible sky. Endless, stony and cracked, the ground is stratified, weathered and powdered with windborne desert sand. In the centre of the rectangle, surprisingly, vestiges appear. Clay bricks, mould-made by hand—just as they were thousands of years ago—and laid with care.12 A strip, of twelve rows and more, recedes from the left towards the centre. There, the direction changes; a new strip makes a right-angled join, continues rightward, and meets the edge of the image. The perspectival arrangement of this large-scale figure, with its smaller internal drawing, causes the pictorial space to appear even deeper. The rough, bare ground in the foreground forms a wedge that positively draws us in. On this vacant area, as a diametrical contrast to the rigid geometric pattern of the bricks, something lies in a confused tangle. To the left and beyond, on the building materials, there are striations that look like cracks: thorns, wire, barbed wire.

This hint shockingly ties in with the line of poetry. Where the painting seemed a moment ago to lead into the wilderness—or was it the place of trial, an area to be traversed, perhaps some rough cradle of humanity?—there is now a sense of oppression and unease, a sense of lurking life. Gypsy: the word stands for the Romantic ideal of a free life outside society and its constraints! Artists identified with gypsies; their songs appealed to wishful fantasies; clichés and illusions attached like burrs to their itinerant lives. But now their camp can never again be a home, a transient place to sleep close to the earth. The word has been stolen. It now belongs to destruction and terror. The word “camp” stands for fear. In the camp, better stay awake; in the camp, sleep is snatched away. Life trickles away, as sand runs out of your hair.

Once more, Kiefer creates a superimposition of ancient, mythic images, archaic vestiges and new, historical experience; but now he leads us into different climatic zones. The grief seems quieter, the language more indirect. Here, the harmony with Ingeborg Bachmann’s poem, and with her essential theme, appears perfect.

The archaeological terrain of another desert scene is less sparse. Brick construction, and the shape of a building whose upper part has been largely demolished, suggest an ancient Oriental ruin. The ruin itself, set back a little way, built in regular courses and with a surface of hermetic uniformity except for the two narrow entrances, is a monumental, dominant presence. It is seen in perspectival recession from near right to far left. Part of the adjacent facade is visible on the right, with remains of buttresses. Above the crumbling debris, and close to the edge of the picture, we read the neatly written dedication, “für Ingeborg Bachmann”. At bottom right, the line “der Sand aus den Urnen” (“the sand from the urns”) runs along the ruts of a passing road. In this case, the dedicatee and the author of the quotation are not identical. The quotation reproduces the title of a book of poems by Paul Celan, published in Vienna in 1948.13 It was there that Bachmann met Celan.14 Kiefer’s painting unites two revered and closely related artists, both of whom died tragically, in a kind of memorial image. The quotation makes it clear that a number of levels of meaning coincide. The ruin motif, the traditional symbol of death and transience, is revived in a new variant: stripped of vegetation, desiccated, a radical image of desolation, of total absence. At the same time, other, oppressive associations enter our minds. The interlocking grid structures of bonded brickwork, which cover the painting, are weirdly reminiscent of later sites of destruction.15 Their rigid pattern, the sign of the ineluctable, disappears only in a few places, beneath smears of clay and sand—a muted metamorphosis. Celan’s verbal image is one of elemental power, which goes beyond consolation. Just as clay bricks were used for the earliest organized settlements, urn burial is an immensely ancient funerary practice. Both the building technique and the ritual are still in use today. The urns, as vessels, symbolize the human body and—another Vanitas motif—also its fragility and impermanence, since they contain the mortal part of it. In Celan’s poem the sand, which is crumbled stone, has left no traces of it behind. Nothing has endured. Nothing will endure. Only art remains to remind us of oblivion.

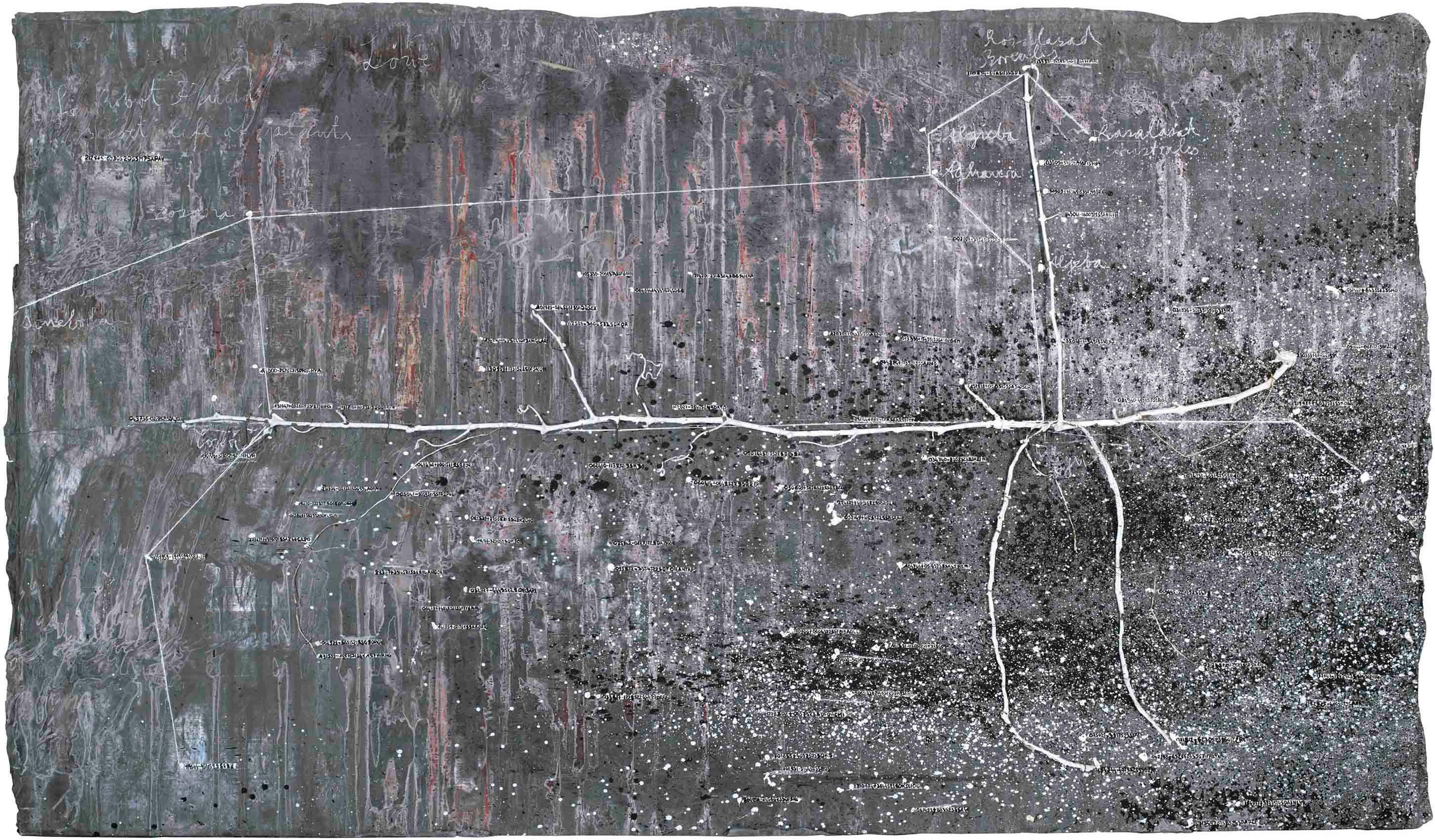

Anselm Kiefer. For Robert Fludd The Secret Life Of Plants, 2001.

In the Cosmos and Star Paintings, unlike the earth-bound desert landscapes, the eye once more turns aloft. No longer suppressed, the sky expands in pictorial space, prompting an age-old question that is also new. In art as elsewhere, since the mid twentieth century, the development of astronomy and space research and the resulting sensational images of the cosmos have endowed the starry sky with an urgent contemporary relevance.

In 1980, Anselm Kiefer depicted himself in a full-length self-portrait, a photograph overpainted in acrylic. Backed by a starry sky, he seems to wade, bare-footed, in the words of a quotation from Immanuel Kant: “Der gestirnte Himmel uber uns, das moralische Gesetz in mir” (“The starry sky above us, the moral law within me”).16 The challenging, contemporary-looking pose and the wristwatch contrast with the timelessness of the crumpled white shirt. This rather touching figure receives a consolidating emphasis from the palette drawn on the chest in black. It radiates like a star; it brings, as it were, the sky into the heart, carrying the philosopher’s maxim home to the artist himself, who thus gains—or offers for discussion—a cosmic point of reference for his own work.

Since 1995, Kiefer has reverted to this cosmic theme in a major and still unconcluded cycle of work. Here, the most recent discoveries of physics appear alongside ancient mythological and astronomical traditions; astral mysticism and philosophical and theological systems blend with poetic interpretation. The dominant motif that emerges is the sunflower. In a group of works initiated in 1996, this is seen as a single head or as several, sometimes associated with the human figure and with inscribed titles such as Sol invictus (Unconquered Sun), sometimes with dedications. Quotations appear, taken from Ingeborg Bachmann, Osip Mandelstam and Robert Fludd. The sunflower never appears as an ornamental plant or—as in Van Gogh’s still-lifes—a bouquet. In its cultivated form, this plant originated in the southern part of North America in pre-Columbian times; it reached Europe in the sixteenth century, via Peru and Spain. Its large, inclined, composite flower-head, with a crown of brilliant yellow corollas surrounding a disc of blackish miniature flowers, the whole mounted on a stalk up to five metres high, gave it the name of Helianthus, sunflower, and predestined it to be a symbol of the heavenly dispenser of light and life.

In Sol invictus, Kiefer shows a sunflower plant at life size; hence the tall, narrow format. He himself is seen reclining beneath it; the unclothed body is highly stylized and seems de-individualized.17 He lies on a cloth, eyes closed, his head close to the lower edge of the painting, his hands resting on his body: dead, asleep, or in trance? Thomas McEvilley has argued that the outstretched, supine pose adopted by the figure in recent paintings by Kiefer corresponds to the position known in Hatha Yoga as shavasana: an exercise in the “checking of the mind” with the purpose of profound renewal.18 The body is turned to the right and foreshortened, thus creating a sensation of space, although the background is open in all directions (the scene is marked as an exterior by the white clouds and the presence of the sunflower plant close to the head). Startlingly, the sunflower does not stand up straight but—frayed and withered and with tattered leaves hanging like ragged garments—bows its great head over the recumbent figure in an anthropomorphic gesture. Out of its black face, however, it has filled the air with its nutritious, dark seeds, and it scatters them over the human being at its foot.

The inscription “Sol invictus” suggests a metaphorical interpretation. If we read this as the name of the Roman sun god whose cult was promoted, notably, by Heliogabalus,19 we are reminded of the darker side of sun worship, the misuse of this emblem of power and radiance. Seen in this light, the blackness in the painting is alarming, and the black seeds that fill the air look like the visitation of a plague. Another interpretation is suggested by the dedication “für Robert Fludd”20 that appears on a number of similar works. This English physician, mystical philosopher and Rosicrucian argued in his works, written under the influence of Paracelsus’ Hermetic and Neoplatonic ideas, that a kind of mystical alchemy—which he regarded as fully equal in status to orthodox theology—could lead to understanding of the universe. Resolutely clinging to the geocentric image of the cosmos, Fludd outlined a system of exact correspondences between the macrocosm and the microcosm. Just as the sun stands at the centre of the macrocosm, the heart is central to the microcosm: “Fludd states that the origin of all things may be sought in the dark Chaos (potential unity) from which arose the Light (divine illumination or actual unity).”21 Fludd’s major theoretical statements are founded on the philosophy of the Neoplatonist, Nicholas of Cusa:22 the principle of coincidentia oppositorum, whereby contraries are contained within each other, and the axiom that the microcosm is made in the image of the universe. Fludd conveys his ideas through powerful visual images,23 and his diagrams of the creation of the universe look like a sunflower. Two instances will suffice to illustrate Kiefer’s interest in this almost unremembered English writer: his treatment of the contrast between light and dark, and his cross-referencing between macrocosm and microcosm. When Kiefer attaches little labels bearing the names of stars to black sunflower heads, seen as if back-lit against bright backgrounds, he is using the flower forms metaphorically, in order to present a view of the sky that reverses the natural state of things: dark stars, white background. This alienation device fascinates, but it also confuses—as does the enigmatic, reclining figure beneath the giant plant. The use of woodcut technique in these works intensifies the contrast and emphasizes the reversal.24 While the names and the connecting lines stand for a systematic and objective handling of the subject, they also evoke visions of the imagination, mythopoetic images; one hears “the noise of time”.25

In 1995–96, Kiefer took up the Romantic topic of night and the starry firmament in a number of overwhelming landscapes.26 The large formats invite us to plunge into alien spaces, in which the encounter between heaven and earth is seen in a new light. Yet, like the sunflowers, they emanate a disquiet that tends to grow. To what extent is everything also its own opposite? Always? White is not to be trusted; sleep can look like death; the stars fall down—black and extinct, as Hildegard of Bingen had her artist show them.27 Intensified by the notion of a totally interconnected macrocosm and microcosm, of an infinitely complex tissue of the universe, for which “our weak capacities” (Fludd) lack the necessary powers of discrimination, the awareness of a universally impending danger imposes itself, stronger than hope, and the paintings acquire a powerful actuality. Many of them reiterate the triadic harmony of the elements, sky, earth and water. But the ascending gaze must return, cast ashore by the tides, into the revelation of the stars in water, entangled in a web of fact and speculation, knowledge and illusion.28 And what are the names of the stars? Alphanumeric combinations, freshly assigned by NASA! These are “authentic”, like the sunflower seeds on the canvas, and among them stand Orion and Taurus, the Bull, the Scorpion—constellations and zodiacal signs handed down from Babylon, Egypt and Greece. Kiefer retraces their shapes and casts a magical web across the teeming background, a celestial geometry with intersections and fixed points. When plant life grows there, or blooms scatter across the dark, the poetic substance of Fludd’s vision unfolds—“every Plant has his Related Star in the Sky”—and the night sky pulsates as the most wondrous projection screen for the human imagination. Where fluttering garments appear among the names, the artist calls them “the Unborn”: an echo of the Platonic notion of the immaterial, pre-existent soul, who flies around until she “at last settles on the solid ground—there, finding a home, she receives an earthly frame which appears to be self-moved, but is really moved by her power”.”29

Lichizwang (Light Compulsion) is the title of the most important painting in this cycle. Centred, diaphanous, written in white chalk, the title stands high above the Milky Way, which rears its soft, cloudy arch across the sparkling firmament. Above left, we read the words “für Paul Celan”. Kiefer thus dedicates his finest Star Painting to the poet. It is monumental, limitless on all sides, with many centres, like Pollock’s multifocal spaces; and yet it remains a celestial map, observing due proportion. We might lose ourselves in dark deeps and feathery nebulae; but there are the fixed points, and a few stars shine more brightly. Their names, like signposts, help us to gain our bearings. Are the lines walkable? Make your way along Cassiopeia and look for the Hesperides. Where is the Great Bear? These lines are puzzling. Almost all are straight; some lead back to the beginning; some break off abruptly. Suddenly, there are the little garments in the centre, floating down. Down to where? Further up, beyond the Milky Way, there is something reddish, like fire, like a trace of blood: Mars, the god of war, is named in big, legible letters. The names, the signs, emphasize the flatness of the surface. They bring us back to the Here and Now.

Lichtzwang is the title of a book of verse by Paul Celan, prepared for press by the poet himself and published posthumously in 1970. It consists of six parts, each containing between eight and sixteen poems. Kiefer never illustrates. It would be wrong to draw an analogy between the bright river that runs across this sky and the river in which the poet assuaged his longing for death. But the idiosyncratically clear and yet enigmatic lines and figures on the firmament, in which ancient mythical images are linked together with numbers and letters, seem to afford a correspondence with Celan’s work. As the poet explained in 1958, “This language—for all its inherent multiplicity of utterance—aims at precision. It does not transfigure. it seeks to measure the scope of the given and of the possible.”30 Kiefer’s dedication reveals how much he values Celan; his title, Lichtzwang, reiterates a word that reflects the poet’s fate.

Notes

1 See, among other works, Max Ernst, La Ville entiére (The Entire City), 1935–36, Kunsthaus Zurich.

2 Cheops is the Greek form of the name of Khufru (a member of the Fourth Dynasty, c. 2575–2465 BC), who reigned for approximately thirty-five years.

3 The uniqueness of the pyramid lies in the perfection of its form, the technical accomplishment of its construction, and its emblematic value as the reflection of a self-contained world-view.

4 Compare the importance of dedications in the work of Cy Twombly.

5 Heinz Peter Schwerfel, “Interview mit Anselm Kiefer”, art 7 (2001), pp. 23, 25: “We would not recognize a poem by Ingeborg Bachmann as perfect, were it not for the mediocrity and absurdity of the world.” Bachmann’s poems “are founded on despair at an absurd world”. “With Ingeborg Bachmann, the tissue of references has become so strong that in my paintings I believe that I am conducting a correspondence with her.”

6 Ingeborg Bachmann, “Das Spiel ist aus”, in Bachmann, Anrufung des GroBen Baren, fourth stanza. See p. 63.

7 Cf. also Anselm Kiefer, Homme sous une pyramide (1996), 354x500 cm.

8 Ingeborg Bachmann, Das Buch Franza, Munich and Zurich 1998, p. 134. This is a separately published volume of Das Todesarten-Projekt.

9 For a synopsis of its genesis, see Bachmann (as note 8), p. 263.

10 “| am again often thinking of the desert, of the moment when laughter returned to me.” Ingeborg Bachmann, quoted by Adolf Opel, Ingeborg Bachmann in Agypten, Vienna 1996, p. 188.

11 See note 6.

12 While in India, Kiefer photographed the making of clay bricks by a technique still in use today. Many of these impressions found their way into his Desert Pictures (Wustenbilder) and Desert Books (Wustenbucher). At Hopfingen, in the Odenwald, from 1988 until the early 1990s, he owned a former brickworks, which he used as a studio, and from which he derived a wealth of imagery. “The attraction of this industrial architecture, for him, probably consisted in the monumental scale of the buildings, the associations with the crematoria of the concentration camps of National Socialism, the ruinous state of the site, and the tangible presence of the elements used in making bricks: earth, water, air and fire.” Ute Fahrbach-Dreher, “Hopfingen wird Gesamtkunstwerk”, Denkmalpflege in Baden-Wurttemberg 2, vol. 27 (1998), p. 84.

13 It is also the title of one of the individual poems. In addition to this cycle, Celan included in the same volume the poem “Todesfuge”, to which Kiefer responded with important groups of work based on the lines “dein goldenes Haar Margarete/dein aschenes Haar Sulamith” (“your golden hair Margarete/your ashen hair Shulamith”). The poems in this volume, which Celan was to republish in his later collection Mohn und Gedachtnis (1952), also included “Der Sand aus den Urnen”. Twenty-two poems from the original set are directly addressed to Ingeborg Bachmann in the second person (marked as such by Celan himself, MS, Literaturarchiv Marbach). Paul Celan (Paul Antschel, Czernowitz 1920 – Paris 1970) was the most important lyric poet writing in German in the twentieth century. He lost both of his parents in concentration camps in 1942–43. Irrevocably marked by the horrors of the Holocaust, he ended his own life by drowning in the Seine.

14 On 20 January 1948.

15 Cf. Anselm Kiefer’s group of works under the overall title of Stone Halls. The traumatic experiences endured by Max Ernst and Hans Bellmer in the internment camp at Les Milles in the South of France found expression in works that incorporate similar brickwork patterns.

16 Immanuel Kant, Kritik der praktischen Vernunft, 1788, in Kant, Werke, ed. Wilhelm Weischedel, Frankfurt am Main 1977, vol. 7, p. 300. The correct wording is “Der bestirnte Himmel Uber mir, und das moralische Gesetz in mir.” Kiefer has involuntarily misquoted Kant’s sentence, which has become a middlebrow bourgeois cliché. Cf. also other works of the same period with starry backdrops, such as: Kleine Panzerfaust Deutschland für Chlebnikow (Little Tank Fist Germany for Khlebnikov) 1980, 83 x 58 cm.

17 Works of 1996 such as Dat Rosa Mel Apibus (The Rose Gives Honey to the Bees), 280 x 380 cm, in which the figure is located at the centre of the concentric circles of a cosmogram, are even more overtly diagrammatic. Cf., e.g., Robert Fludd, Utriusque cosmi maioris scilicet et minoris Metaphysica, physica atque technica Historia. Tomus primus, De macrocosmi Historia in duos tractatus diuisa, vol.|, Oppenheim: De Bry, 1617, title page.

18 Thomas McEvilley, “Communion and Transcendence in Kiefer’s New Work: Simultaneously Entering the Body and Leaving the Body”, in Anselm Kiefer. I Hold All Indias in my Hand, exh. cat., Anthony d’Offay Gallery, London 1996. He here refers to Patafijali (Yoga Sutra 1.2).

19 Cf. Anselm Kiefer, Heliogabal, 1974, watercolour, 30 x 40 cm, and Sol invictus Helah-Gabal, potato-print book, 1974.

20 Robert Fludd (Robertus de Fluctibus), Bearsted, Kent 1574 - London 1637. In his world-view, as described most notably in his magnum opus, De utriusque cosmi, which is not based on astronomical calculations, Fludd combines Neoplatonic, theological and alchemical notions. His stubborn adherence to the geocentric world-view was criticized, notably by Kepler in 1619 and 1622.

21 A. G. Debus, “The Sun in the Universe of Robert Fludd”, in Le soleil a la Renaissance. Sciences et Mythes: International colloquium, Brussels 1965, p. 266.

22 Nikolaus von Kues (Nikolaus Chryfftz or Krebs, Kues/Mosel 1401–1464 Todi). In his treatise De coniecturis (On Conjectures), c. 1440, he set out his theory of four levels of cognition in two diagrams: “The Figura Paradigmatica represents the universe through the interpenetration of two pyramids, the bases of which he names Unity (unitas) and Otherness (alteritas). In these two, he says, all other oppositions are contained: God and Nothingness, Light and Darkness, Possibility and Reality, General and Particular, Male and Female. Ascent and Descent, Evolution and Involution, are one and the same. The advance of one is the retreat of the other.” Alexander Roob, Das hermetische Museum. Alchemie & Mystik, Cologne 1996, p. 274.

23 Flood (as note 17), illustrated in the Oppenheim ed. of 1617 by Matthias Merian.

24 In his early work, Kiefer made a decisive contribution to the revival of this technique and its use on a monumental scale in contemporary art.

25 Osip Mandelstam, The Noise of Time, San Francisco 1986; in German, the phrase is “das Rauschen der Zeit”.

26 See, among others, Cette obscure clarté qui tombe des étoiles (This Dark Light Falling from the Stars), 1996, 480 x 430 cm; Die Sechste Posaune (The Sixth Trumpet), 1996, 520 x 560 cm.

27 St Hildegard of Bingen, Liber Scivias, Book III, Vision III.2, The Almighty and the Extinct Stars. Rupertsberg MS, twelfth century.

28 On the nature of the lines drawn to link the stars, or the flowers that stand for stars, see, among others, Anastasius Kircher, Ars magna lucis, Rome 1665. The rays of light stand for degrees of enlightenment.

29 Plato, Phaidros, 25, 246, c; quoted from Plato, Phaedrus, trans. by Benjamin Jowett.

30 “Dieser Sprache geht es bei aller unabdingbaren Vielseitigkeit des Ausdrucks, um Prazision. Sie verklart nicht, . sie versucht, den Bereich des Gegebenen und des Moglichen auszumessen.” Paul Celan, “Antwort auf eine Umfrage der Galerie Flinker, Paris (1958)”, in Celan, Gesammelte Werke, vol. 3, Frankfurt am Main 2000, p. 167.