On the Sociological Position of the Graphic Designer

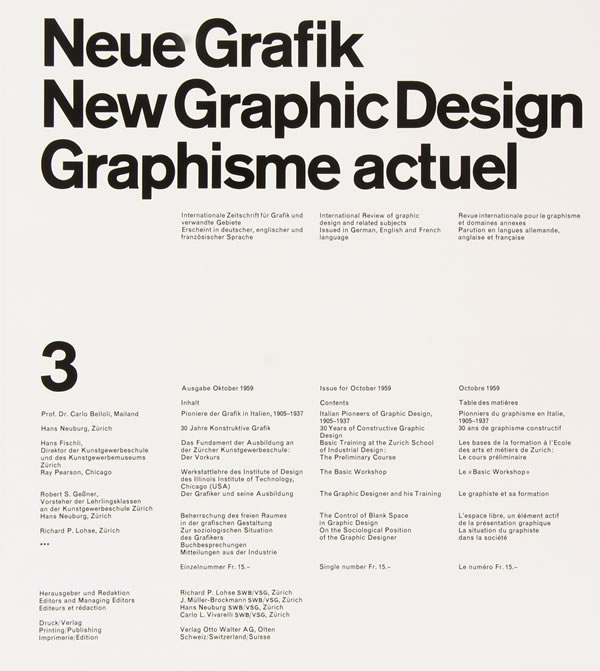

Neue Grafik, 3, October 1959.

There is no doubt that advertising design as a means of effecting sales registers certain intellectual and economic as well as, of course, social conditions and that is a compelling if not a complete expression of the attitudes and appetites of a particular epoch.

Advertising or industrial design, from what we know of its development, owes its existence to the industrial and economic revolution of the 19th century, the prodigious expansion and immense changes in the market resulting from that revolution and the consequent ruthless competition. Advertising design is inextricable bound up with the conditions of free competitive trade; it must boost and sell the products which are put on the market, either in answer to a demand or to create a demand, as a result of economic structure. We have for long been aware of the decisive effect of alternating prosperity and crises and of the importance of economic conditions. This is the age of machine-made goods and chain stores; mass production is really the ideal of the industrial society of the present.

No one can remain aloof from the powerful effect of forces organised on so vast a scale or escape the tremendous pressure and all-pervasive influence of the cycle of production-consumption-production. The realisation of these facts makes us sharply aware of the reality with which the graphic designer is confronted. Even if we concede that there are individual cases in which freedom of choice does exist to a certain extent and where it is possible to make a creative contribution, we have to acknowledge that industrial design must of necessity conform to the conditions which gave it birth and must take a different form from that the graphic arts assumed in the period when individual work was done by hand, when there were no standard proportions and the spirit of the age was adequately expressed by symmetrical typographical designs and copper-plate engravings of pastoral idyls.

Although the graphic designer to some extent resembles the artist who worked by hand under the earlier economy in that he has his own individual methods of working, as a practitioner of his particular profession in his present sociological position he is as much subject to economic conditions as the advertising consultant who occupies an important position in the economic system. As the creator of something which can be reproduced in unlimited numbers he is also clearly differentiated from the former graphic artist carrying out his own work by hand.

Intensification of the processes of production, the necessity of employing new advertising methods to reach new strates of consumers will doubtless also have an effect on the position of the graphic designer, altering it in accordance with the wider range of machines. The continually increasing mechanisation of methods of production, the ceaseless rotation of identical parts, automatically in fact, will necessarily call for new methods of advertising and bring into being a new type of graphic designer.

An understanding of the intellectual and economic situation shows brings a realisation of how much the existence of the graphic designer as a creative being is threatened by the present age, how greatly he is exposed to its temptations to its existence on tangible results and, not least, how easily he may succumb to the economic and social allurements it holds out. Let us try to imagine the moral effort required on the part of the designer who has committed himself to a progressive style if he is to fulfil the purely economic conditions of a commission. An artist who was aware of the extent of the pressure brought to bear on him, would have to be completely objective to bring his own methods of work and his own creations into tune with the intellectual climate of the times in which the product was to be made and marketed, and to adjust the effort he expensed on a piece of work to its market value.

The professional status of the graphic designer changes according to economic contingencies and crises. If we acknowledge therefore with some hesitation that our fate is controlled by the economic situation, the responsibility of the individual and the difficulties of decision must be all the greater. The deluge of mass-produced goods sweeps away aesthetic considerations; they have become subservient to an authority set up by sheer weight of numbers and by the power of tangible success, a very unaristocratic authority therefore.

Let us look back for a moment. Formerly taste was dictated by the aristocracy, today it is in the hands of anonymous companies who wish the graphic designer to use his aesthetic sensibilities to further the sale of some commodity by giving it voice and form. His social position is bound up with his work and subordinate to it and he shares this situation with the architect and the pure designer for their tasks also are directed towards a particular object and are determined by the nature of the commission. The work of the graphic designer has a far wider influence in every day life than that of the free artist, but the regard in which it is held is related, like that of any other commercial product, to continually changing demands, and apparently diminishes far sooner than the esteem accorded the architect. The gratuitous publicity, the ephemeral importance which are extended to the graphic designer’s work sometimes produce a feeling of guilt towards the art to which, because it is so readily accessible today, the graphic designer owes most, but which is only acceptable to society in the useful form it takes in advertising and which is cast on one side once the glamour of modernity has lost its economic value. For conditions of work it is doubtless an advantage if the industrial designer need not always be aware of his position midway between fine and applied art.

As a creative artist the graphic designer naturally avails himself of the formal inventions of progressive art, but by investing the commonplace with these formal qualities he often pays the price of being forgotten. This has been the characteristic fate of many pioneer graphic designers and typographers. Thus the pioneer designers of today, like the products on behalf of which he works, is at the mercy of the forces controlling supply and demand. Unlike the progressive artist most graphic designers tend to go under in a period of spiritual or economic pressure.

Is it because he is a particular type of person or is his background which leads a young man with a certain degree of visual and intellectual sensibility to put that sensibility on the market? The graphic designer is doubtless so constituted that he finds it easier to achieve a position in society by carrying out and identifying himself with work which has a definite objective than by adopting the independent attitude of the artist. He is committed to the execution of the commission and devotes himself wholly to the problem of giving the work aesthetic form and of establishing a synthesis between an objective, the motive for which lies outside his own sphere, and his sensibility.

At this stage of our enquiry we must ask the the difficult, if not brutal question as to whether, where certain products are concerned, the more advanced forms of graphic design do not merely play the titivating role which cosmetics assume in the world of fashion. In assessing the value of the graphic designer’s work we must nevertheless keep count of how much artistic ability, moral powers of resistance and knowledge of continually changing cultural and psychological conditions are necessary in order to produce results which will stand up to the harsh judgement of contemporary criticism. The mental attitude of the best graphic designers is conditioned by this tormenting state of tension which increases where there is greater aesthetic feeling.

The graphic designer is continually called upon to play the part of the instrument of the ruthless combination of production, sale and profit. As an executive he is on the one hand a creative artist and on the other a public relations man rigidly controlled by the nature of his commission, working intuitively, apprehensively and with torn convictions to fasten his own artistic aims upon an alien product.

The free world of art is open to few and even they may be mistaken if they regard it merely as a form of escape. The fact that painters of the younger generation scornfully refuse to earn their living as typographers or existing on grants and private charity is a definite symptom of the decadence of the present age. The position of the graphic designer is quite different. His achievement is less spectacular but often of greater profundity, shows more sense of responsibility and is more sincere despite the trivial purpose for which it is intended, than the products of a misunderstood romantic expressionism, the late fruits of an individual type of artist who although favoured by an industrialised society refuses the challenge of a responsible art.

The feat of producing authentic and sincere work in the face of the alternatives offered by the present day is not to be lightly esteemed. If we are aware of the far-reaching connections between economics and human existence we cannot but clearly realise the responsibility which is laid upon the graphic designer as upon the architect, as a creator of form and as a propagandist for the everyday needs urged upon us by our system of economy. This responsibility is particularly obvious when the creative designer opposes the customary practice of persuading by false means and supports the opinion that he must convince the buying public by purely objective means.

Richard Paul Lohse

Magazine article in: Neue Grafik / New Graphic Design / Graphisme actuel

Editors: Richard Paul Lohse, Josef Müller-Brockmann, Hans Neuburg, Carlo L. Vivarelli

Nr. 3, October 1959, pages 59. Text also in German and French.