Kiefer as Occult Poet: Frances Colpitt

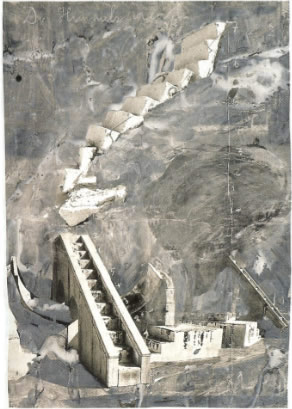

Anselm Kiefer. The Heavenly Palaces, 2003.

From the beginning, reaction to AnseIm Kiefer's work has been polarized. His remarkable early success, and enthusiastic acclaim by museums and collectors, soon produced a backlash. The critical left (Benjamin Buchloh, notably) dismissed him as a commercially well rated purveyor of a bombastic nationalistic style. But for others, especially artists, his works that embrace earthy organic materials, with their dense physicality and loaded content—ranging from meditations on the Holocaust to the mysteries of creativity—presented revitalised and expanded possibilities for painting. In short, the cultural and personal expressiveness of his art appeals, or doesn't, depending on one's tolerance and taste. In a review of Kiefer's 2005 exhibition at White Cube's temporary annex In London, Adrian Searle concluded in the Guardian that “Kiefer’s art is as ambitious as it is magnificently grandiose, uncomfortable and brooding. His work is as deeply troubling as it is impressive—and that is as it should be” Nearly 20 years ago, Peter Schjeldahl similarly observed the "hedged awe" that greeted Kiefer's work, a response he referred to as “Anselm Angst" on the occasion of the artist's only major American retrospective until now. The still unsettled opinions about Kiefer's reputation make his work a ripe subject for a second investigation by an American museum. Organised by Michael Auping, chief curator of the Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth, "Anselm Kiefer: Heaven and Earth" offers an opportunity to revisit these controversies and assess the endurance of the work, which has remained fairly consistent in style and subject matter.

Kiefer, who was especially prominent during the heyday of Neo-Expressionism, studied law before becoming an artist in the late ’60s. Although not officially a student of Joseph Beuys, Kiefer sought him out in Düsseldorf and acknowledges the spiritual influence of the older artist, Kiefer's earliest paintings were produced in a former school-house in Germany's Oden Forest, where he lived until purchasing an abandoned brick factory near Buchen in the 1980s. The schoolhouse and factory inspired, and are depicted in, many of his paintings, and the same is true of his current 200-acre studio complex in Barjac, in southern France. On the grounds of this former silkworm nursery., the artist has erected massive architectural installations and cultivates giant sunflowers. According to Auping, the sunflower seeds used in several of his recent paintings pay homage to Vincent van Gogh, whose sunflower paintings were produced nearby.

“Anselm Kiefer. Heaven and Earth" includes more than 60 paintings sculptures and books, the exact number of which will vary during the show's tour It begins with Kiefer's earliest extant works, from 1969, and concludes with 10 pieces from 2005. All were aptly chosen to exemplify the show's theme, which not only reflects one of the artist's primary interests but avoids, in most cases, the more controversial references to the architecture of the Third Reich and the battlefields of World War II that occurred so frequently in his early work. By organizing a survey of considerable scope that eliminates Kiefer's most antagonizing work, Auping argues for a revised assessment of his output to date. That being the case, the catalogue and didactic wall texts are crucial components of the exhibition—and they pay almost no attention to formal issues and little to material concerns.

Such a heavy emphasis on iconography tends to limit rather than expand the paintings' possible signification. The lengthy interpretation of Die Milchstrasse (The Milky Way), 1985-87, is a prime example. The painting depicts a ravaged landscape in thick patches of Kiefer's signature material, a pasty compound of emulsion, oil paint, acrylic paint and shellac. Suspended below a high horizon line, set deep into illusionistic space, is a hand-fashioned lead funnel inscribed with the word Alkhest (an alchemical solvent supposed to induce material transformation). As if extruded from the funnel's tip, a long horizontal white gash that literally cuts through the built-up paint contains the words die Milchstrasse. In an interview with Auping that is printed In the catalogue, Kiefer identifies "the cut in the land as a puddle of water.” Elaborating on Kiefer's interpretation of the Milky Way as “a puddle In the cosmos," the catalogue entry and wall text describe it as "a puddle in a much vaster universe" while the "milky golden light' suffusing the atmosphere of the painting is (metaphorically) the result of alchemical transformation. Furthermore, Auping's wall text tells us that Kiefer is alluding to a Greek myth which attributes the creation of the Milky Way to Hercules, who "sucked so violently on Juno’s breast that her immortal milk sprayed across the heavens.” It is hard to see how the deployment of such arcane stories and archaic belief systems in the construction of meaning could possibly support the painting’s credibility. More helpful would be an approach that considers the drama and emotional power of the work, its theatrical scale and evocative materials.

The symbolic interpretation of a related work, the Walker Art Center's Die Ordnung der Engel (The Hierarchy, of Angels), 1985-87, is similarly mystifying. With a crusty surface in shades of ocher, sienna and black, the painting described by the Walker as a "beach scene” is identified by Auping as a "celestial space.” A huge handmade lead propeller in suspended in front of gently lapping waves of white paint in the top portion of the painting. Hanging from wires are chunks of what the checklist calls "curdled lead" (Kiefer is secretive about his techniques) with cardboard labels naming the angelic orders (Seraphim, Cherubim, etc.). Following the titular reference to Dionysius the Areopagite, who conceived of the hierarchy of angels in the fifth century, the wall text asserts that the "large rocks, or 'meteorites' as the artist calls them, stand in for angels." Ethereal messengers of God symbolized by rocks? Auping accepts Kiefer's invitation to make symbolic equations that ignore Panofsky's advice on iconography: "If the knife that enables us to identify a St. Bartholomew is not a knife but a cork-screw, the figure is not a St. Bartholomew."

Interpretive quibbles aside, the exhibition provides a captivating overview of Kiefer's fearless experimentation with materials and his command of scale, from the operatic to the intimate. As a foil to the high-strung nature of much of the work, "Heaven and Earth" was spaciously and harmoniously installed in the upstairs galleries of the Modern Art Museum, The first room introduced Kiefer's career with important paintings of the 1970s, including Mann im Wald (Man in the Forest), 1971, a washy oil painting on canvas, similar in its handling to the numerous watercolors included in the show. It depicts a figure we're told is the artist, holding a burning branch in a dense forest. Another forest, an early favorite symbol of Kiefer's, is home to a snake in Resurrexit (1973). The snake reappears In a depiction of the interior of the artist's famous former studio, a wooden schoolhouse attic, in Quaternitat (Quaternity) of the same year. Labeled "Satan," the snake is accompanied by three flames identified in handwriting on the canvas as the Trinity, a more widely legible symbolism based on art-historical as well as religious traditions. Two unusually small landscape paintings (slightly larger than 2 by 3 feet) contain crude outlines of a palette, an image that reappears in Himmel-Erde (Heaven-Earth), 1974, where it encompasses a rough and awkwardly painted earth and sky also connected by a vertical line labeled malen (to paint). Though it is possible to see this work (as Auping does) as a statement about the character of the artist, Kiefer's use of a word that is a verb rather than a noun denotes an activity rather than an identity.

Kiefer's earliest existing work takes the form of books, a medium still central to his career. This exhibition contained two paperback-size scrapbooks from 1969, both called The Himmel (The Heavens), with spare, collaged and painted elements applied to their yellowed pages. Of the many other series of books in the exhibition, Ausbrennen des Landkreises Buchen (Cauterization of the Rural District of Buchen), 1975, is the densest and most oppressive. The seven volumes consist of burnt burlap pages, which, a wall text says, were made from rectangular remnants of paintings previously destroyed by the artist. The black charcoal-encrusted pages are thick and opaque, conveying a sense of physical weight that is also heavy with personal history. In Elektra (2005), the pages (like the 1975 book, they are roughly 2 feet high) are treated similarly, serving as supports for lumpish organic materials rather than printed or written words. But here, the sensibility is lighter and less steeped in obscurity. Caked with red-dish clay and sand, the pages suggest landscapes of cracked earth with the artist's habitual high horizon line. Material accumulates at the bottom of each.

Another use for the book appears in 20 Jahre Einsamkeit (20 Years of Solitude), 1971-91. The sculptural ensemble consists of seven pallets placed on the floor, each stacked with curling sheets of weathered and paint-spotted lead salvaged from the war-damaged roof of the Cologne Cathedral. Six of the lead sheets support open store-bought ledgers; a closed handmade book rests on the seventh. All the books are stained with brown spots identified in the label as the artist's semen. The Secret Life of Plants (2001) depicts what Kiefer refers to as "the scientific heaven” in the form of a 6 1/2-foot tall book, standing on end, with its lead pages fanning out to a 10-foot diameter. The corroded surfaces support painted patches inscribed with NASA star numbers, which are in turn connected by painted lines. The ample scale allows the viewer to almost literally walk into the universe.

Several of Kiefer's most recent paintings are seascapes, not landscapes, and seem influenced by the quality of light characteristic of a different, Gallic climate and landscape. Aschenblume (Ash Flower). 2004, is one of the exhibition's standouts. Above a dark roiling sea floats an ominous black cloud stained, inkblot-like, onto the canvas. A brilliant, vaguely Impressionist light glows from between the cloud and the distant horizon line. Lowering the horizon to the center from its normally high placement in his work, Kiefer mitigates some of the tension and instability, if not the foreboding quality, that are typical of his earlier paintings. While the cloud conjures up thoughts of brewing storms or apocalyptic explosions, a lead grid, recalling a mullioned window, is placed on top of the cloud and establishes a sense of flatness in an otherwise illusionistic painting. In Melancholia of 2004, the windowlike element is replaced by a murky glass object in the shape of the famous polyhedron in Durer's Melencolia I. A gaseous white cloud appears behind the polyhedron. while a thick mixture of brown-, black- and gray-tinted emulsion on the lower half of the painting suggests either a parched landscape or, contradictorily, a disquieted ocean—the brooding seascapes of Albert Pinkham Ryder writ large. These seascapes (and a third) seem intended for meditative rather than expressive purposes. They are occasions for relatively free perceptual experience rather than a guided process of narrative interpretation. An atmospheric luminosity also characterizes Klefer's newest landscapes—many of which, despite the curator's premise, refer explicitly to armed conflicts. The attached materials and palette of dusty terra-cotta, taupe and warm gray call to mind the war-infested deserts of the Middle East. Like vicious tumbleweeds, tangled masses of razor wire are strewn over the cracked and abraded surface of the 18-foot-wide painting Himmel auf Erden (Heaven on Earth), 1998-2004. The title of this monumental landscape is more likely based on wishful thinking than on irony. La Conversion de Saint Paul (2005) Includes a toy-size military tank, handbuilt from clay, suspended over a representation of an arid landscape. Behind the tank, a rust-colored explosion and a splash of aluminum paint erupt like the clouds above Kiefer's seascapes. Along with the references to war, Caravaggio's memorable depiction of Saul's fateful conversion to Paul—that is, to Christianity—is invoked by the upside-down position of the tank.

Die Himmelspaläste (The Heavenly Palaces), 2002, one of three works here with that title, is over 20 feet tall and depicts the interior of a golden colonnade above which vaults an elliptical lead surface inscribed with a star map. Because of its size, the painting was hung on the ground floor of the Fort Worth museum and was visible from a balcony on the second floor, where the great mass of molten lead flowing into the temple could be seen as a majestic open sky. Die Himmelspaläste of 2003 Is one of a series of gouaches on torn photographs some of which depict the several sets of monumental cast concrete stairs that Kiefer has placed around his land in southern France. Obscuring much of the silvery prints' imagery with dripped and smeared gray-toned gouache, Kiefer isolates the stairs so that they seem to float above the photographed land or water. In some cases, the stairs lead upward Into the sky; in others, they are stacked on their sides, their interlocked teethlike steps suggesting tank treads. Downplaying Kiefer's explicit references to difficult passages in German history, Auping draws attention to the artist's longstanding, and often overlooked, interest in mysticism. The theme appears to have inspired Auping's well-meaning attempts to interpret the work based on the artist's complicated iconography. Issues of the intentional fallacy aside, this sweeping survey demonstrates the artist's serious devotion to life's big issues.